When I mentioned that I’d been playing a new strand game, indie developer Strange Scaffold’s Witch Strandings, in TheGamer’s Slack, I got all manner of reactions. Fellow features editor Eric Switzer revealed that he regularly asks developers of triple-A titles if their games are strand games, editor-in-chief Stacey Henley argued that Pokemon Legends: Arceus’ satchel retrieval made it a strand game, and one colleague who shall remain nameless earnestly asked what a strand game actually is.

They had a point though, what is a strand game? The first port of call is Hideo Kojima himself, the man who coined the term and created Death Stranding, which up until recently was the only strand game in existence. “DEATH STRANDING is not a stealth game,” he says in his initial tweet revealing the genre. “It is brand new action game with the concept of connection (strand). I call it Social Strand System, or simply Strand Game. [sic]” Understand the concept now?

While Kojima is being characteristically cryptic about what a strand game actually is, Witch Strandings developer Xalavier Nelson Jr. told Kotaku that he believes there are three core pillars to the strand genre and connection is none of them. The first principle is the concept of nurturing, and the fact that your main goal is to take care of the world you inhabit, or at least improve it for others. Death Stranding is, at its core, about connecting people and communities, and Nelson believes this to be of equal importance to the strand concept as any connection between players’ games.

The second of Nelson’s strand principles is transportation, which seems fairly obvious, but goes deeper than you may think. He argues that your transportation has to “actually change the world,” making the act of walking into more than just a fetch quest. Transportation also needs to be the game’s core mechanic, rather than combat. The final principle is physicality. In Death Stranding, that’s presented by the tower of packages on Sam Porter’s back and the minute differences in the terrain, but that’s a mechanic much harder to replicate on an indie budget.

Budget comes into Nelson’s definition of the strand genre often. Defining the genre as Kojima’s web of interconnected players or Legends: Arceus’ lost satchels would leave the genre inaccessible to any developers other than triple-A, and the latter’s basic Dark-Souls-message-esque system is hardly an imaginative representation of the genre mechanic in an otherwise strandless game.

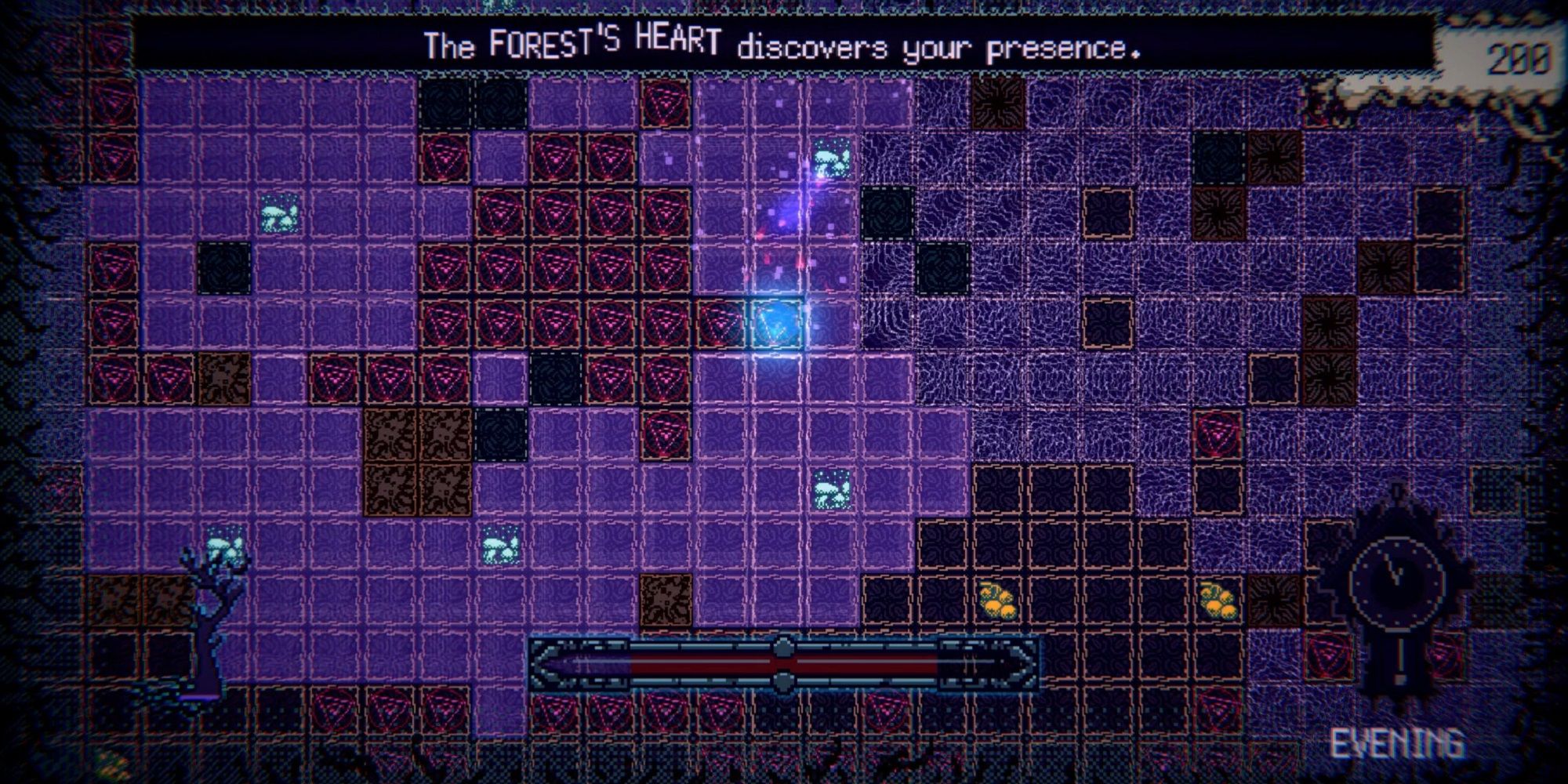

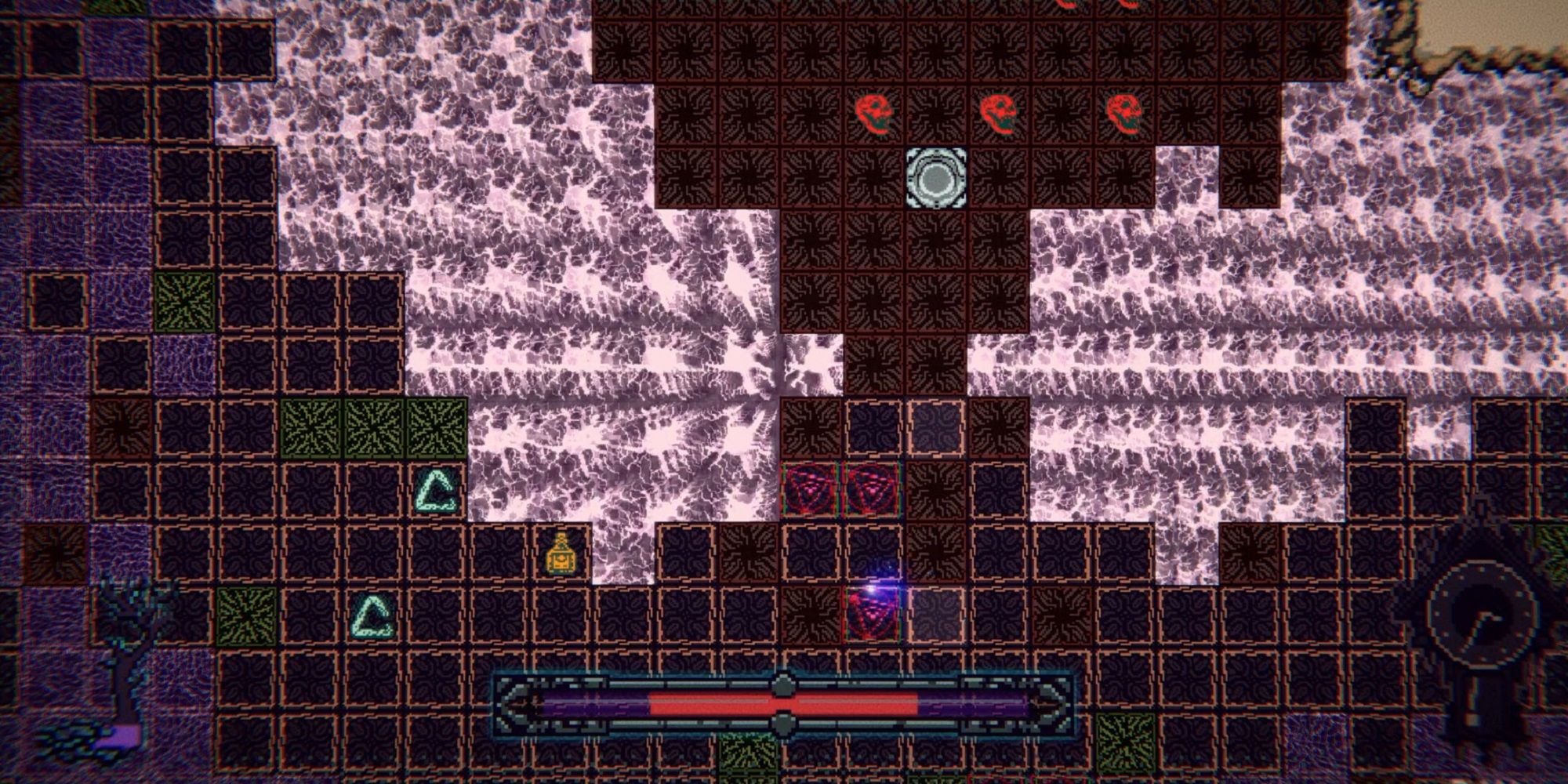

Witch Strandings is the opposite of Legends: Arceus, reimagining the strand genre on a far smaller budget and diving deeper into the concepts behind Death Stranding as a result. Instead of having a player character, you are trapped in a dark forest, and must use your mouse to navigate through its puzzles and challenges. The forest itself is presented as top-down tiles, with different colours and patterns representing swirling rapids, poisonous thorns, and dangerous quicksand. It’s a far cry from the realism of Death Stranding, but nails the execution of nurturing, transportation, and physicality.

The three principles are impossible to describe separately, as almost every aspect of Witch Strandings embodies all three. You control a small mote of light, the heart of the forest, with your mouse. You can heal parts of the forest by moving items – a gnarled staff clears an area of quicksand or hexes for as long as it remains in range – which allows you to travel through. If you’re caught in the quicksand, however, your mouse movements become slow and sluggish until you escape or perish. This dissuades you from rushing through the forest with wide, sweeping mouse motions, and instead you mostly opt for smaller movements that allow you more control and precision.

The physicality of Witch Strandings is my favourite element, as it feels like a real, physical chore to escape from quicksand or untangle yourself from thorns. It plays an important role in the strandness of the game too, though, as your staves and mushrooms that ward off obstacles stick around after you die, each round opening the forest further and inviting you to sweep your mouse across your entire desk as you explore more freely.

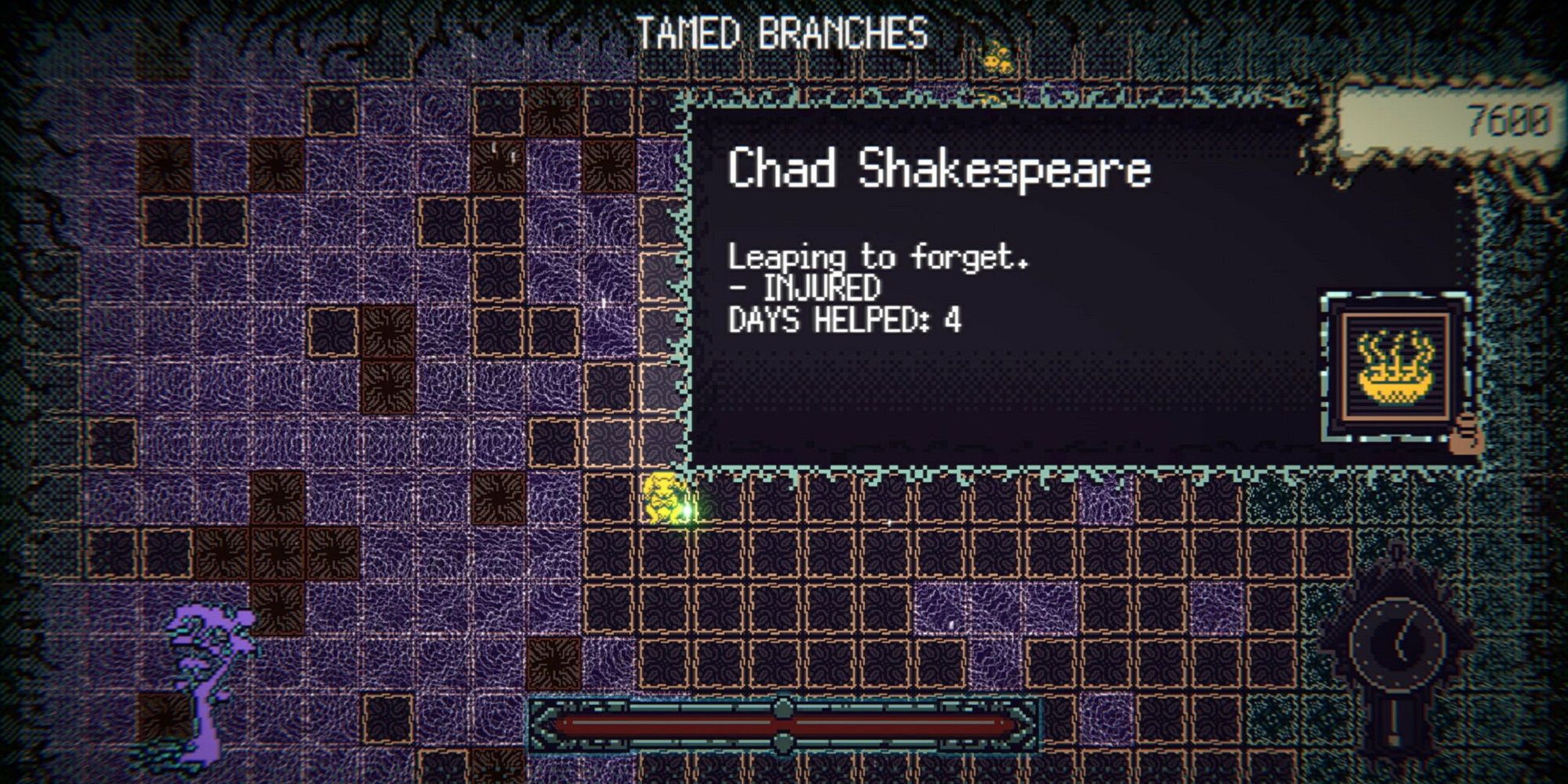

Much like Death Stranding, its indie counterpart’s simple plot is advanced through exploration and interaction. Talking to NPCs, animals inhabiting the forest, gives you a sense of the eponymous witch’s corruption, and from there you can choose to help them or not. Find a berry to feed a hungry frog or figure out what will heal an injured fox – or don’t – as you navigate through the forest to cure it of its sickness. Chad Shakespeare, a dog bro who has appeared in Nelson’s other games An Airport for Aliens Currently Run by Dogs and Space Warlord Organ Trading Simulator, makes another appearance as one of the forest’s inhabitants.

The forest is colourful tiles rather than painstakingly placed cliffs, crevasses, and pebbles, but that doesn’t make it any less of a strand game. Your strands weave through the forest, forging permanent pathways between different areas and connecting characters to their needs. You’re nurturing the forest, transporting items in order to explore further or help others, and the effort of doing so is incredibly physical. Who cares if your strands don’t connect to other players on top of all this?

Having pondered both Kojima and Nelson’s definitions, I think that the most crucial element of a strand game might be that you call it a strand game. What Witch Strandings lacks in budget it makes up for in imagination, and its simple premise is a deceivingly complex reimagining of the genre. If you still think Legends: Arceus or city builders are strand games after this article, however, I beg you to broaden your horizons and embrace more creative approaches to the genre.

Source: Read Full Article