It’s very easy for a folk horror piece to feel too overwrought or transparent. You’ll have cultists hiding in plain sight, a creepy old man who drones on about “the old ways”, or an enormous wicker man, for some reason. These images don’t evoke feelings of unease and dread when you’re bashed over the head with them, killing any semblance of suspense.

Despite being a relatively short adventure game, The Excavation of Hob’s Barrow manages to avert these pitfalls and crafts an unsettling experience that never feels hokey. The premise is standard for a folk horror. You play as Thomasina, an antiquarian writing a book about barrows in rural England, who visits the northern village of Bewlay thanks to the promise of an interesting dig. What follows is your standard adventure game fare – explore the area, collect various items, and solve puzzles, usually helping out the standoffish locals in the process.

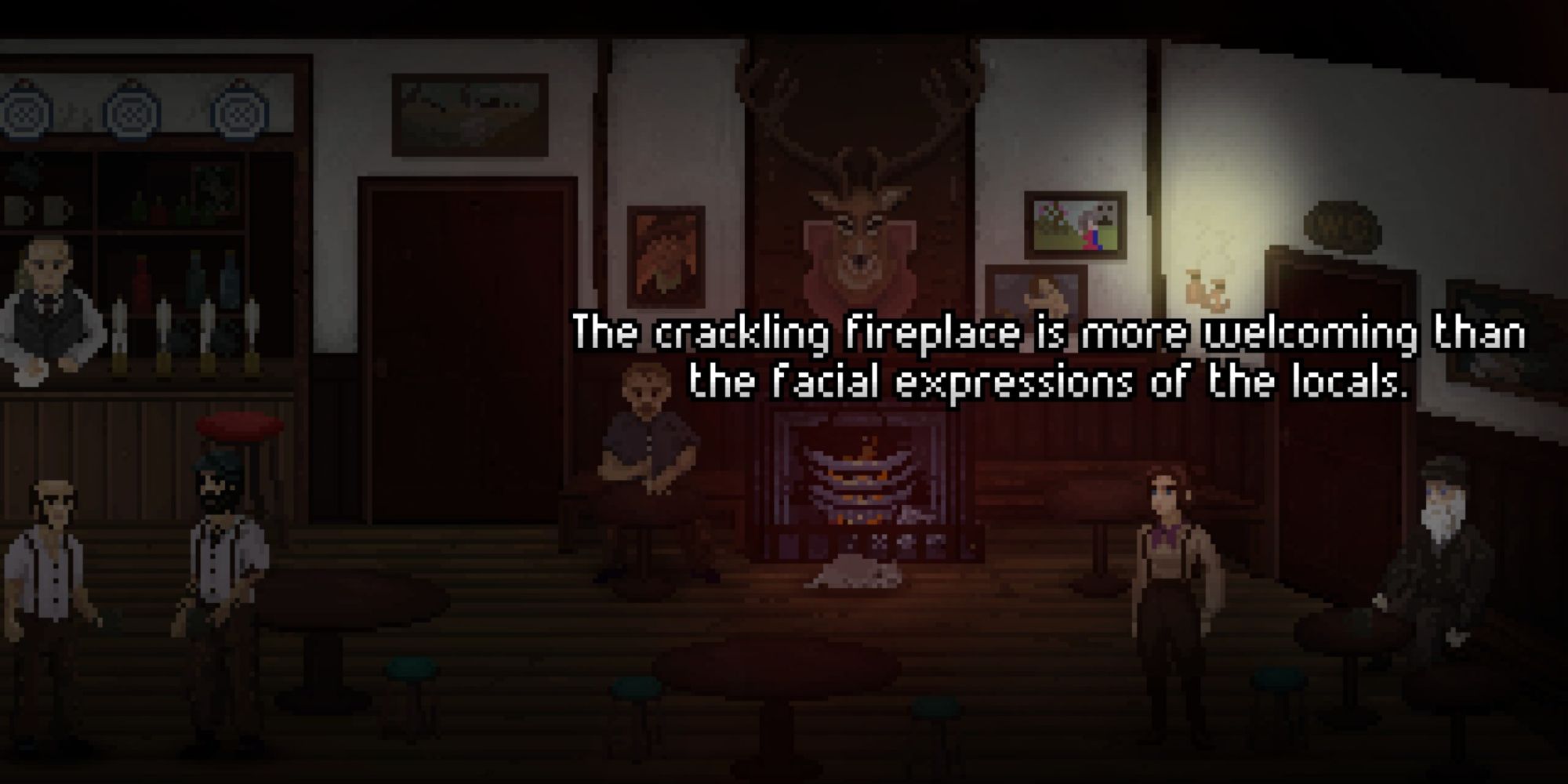

The way Hob’s Barrow instills horror is understatedly effective. What would be a typical adventure game story is punctuated by off-kilter moments. In an early example, you come across a priest stumbling through the forest, who begs you to cut his arm open in an act of bloodletting to alleviate his delirium. After this, Thomasina starts having disturbing dreams. You get drip-fed legends about a goblin, and the tragic past of Hob’s Barrow gets revealed to you piece by piece. The horror ramps up slowly and gradually, with no cheap jump-scare or gore tactics – it’s distilled unease through and through. Adding to this is how rural and isolated the town of Bewlay is. You are constantly reminded that you are an outsider, and they don’t like no outsiders in Bewlay, to the extent that even the construction of a train station linking the village to the outside world is the subject of ire.

A lot of the time, you’ll find that you’re second-guessing yourself. Thomasina is a proud and, above all else, rational woman, and many perceived threats turn out to be harmless. The ‘witch’ who lives in the forest is simply an old woman who knows how to make herbal remedies. The monster in the burrow is just a wild animal protecting its den. The goat is just a goat (I mean, what did you expect?), albeit a goat that likes to act violently. You’d think this would lull you into a false sense of security, but something about Hob’s Barrow keeps you on your toes – it never lets you feel truly safe.

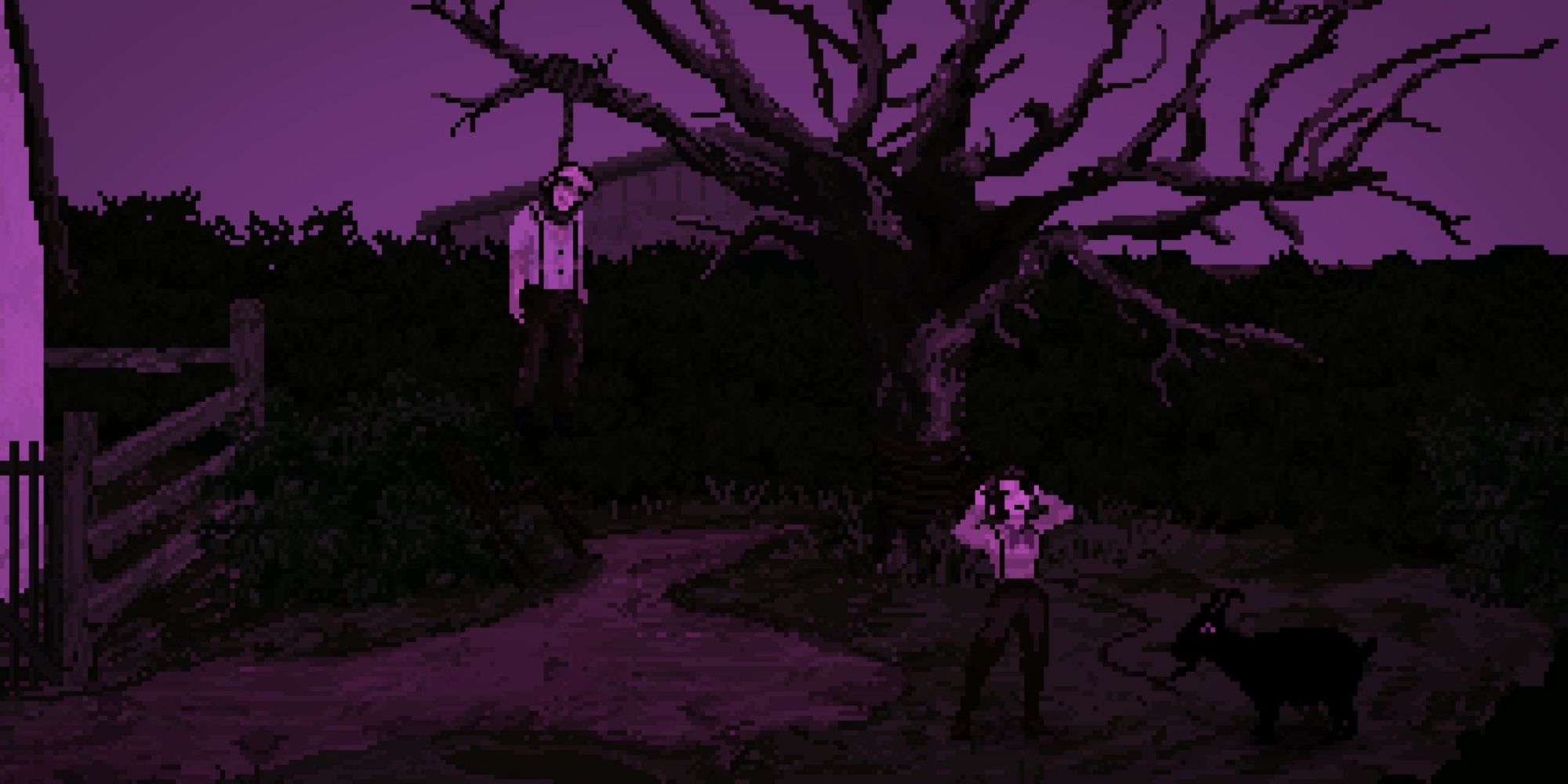

The pinpoint pricks of unease get sharper after the midpoint. You find a missing man tied to a post, his mouth stuffed with hellebore, you can fix a mute girl’s fiddle, and she gives you a haunting performance that leaves you unconscious, and you learn that Thomasina has a stronger connection to Bewlay than even she knew. The mundane is replaced with the extraordinary with more regularity.

As you reach the climax of the game, Hob’s Barrow leans in on the ‘folk’ part of folk horror, and embraces its inspirations and references. Entities from Gnosticism and Paganism are confirmed truths and Thomasina both witnesses and takes part in supernatural rituals that the rational mind wouldn’t even consider. While the scenes and revelations at the end of the game are flashy and shocking, the most interesting way the game evokes horror is in its buildup.

Thomasina performs some truly out-of-character actions, but they’re what the entire game has been leading up to – her world of rationality and science is torn down brick by brick. The main threat is a powerful pagan god, sure, but the scariest thing is how Thomasina finds herself in an impossible situation, surrounded by people who would manipulate her, while isolated in the moors of northern England. In Hob’s Barrow, the cultists are discrete, the old man’s words were subtle, and the wicker man is a centuries-old barrow holding a pagan god.

Source: Read Full Article