The Batman is a surprisingly grounded film. Superhero movies have become so obsessed with world-ending threats and larger than life adversaries that when the stakes are brought down to a human level it can feel underwhelming. There isn’t a generic beam of light bursting into the sky that our heroes need to stop, so there’s a chance that mainstream audiences might grow bored and zone out completely. Here’s looking at you, Suicide Squad.

When I heard that Robert Pattinson’s turn as the caped crusader was pushing three hours in length, my initial fear was that it would attempt to be a pretentious and overly indulgent slice of detective drama that fails to recognise the appeal of the character and veers much too far in the opposite direction for its own good.

It is certainly overlong and oftentimes ponderous, but The Batman is so brilliant because it understands the past successes of Nolan, Snyder, and even Burton while seeking to weave a narrative unlike anything we’ve seen in the genre before. It’s brilliant because it doesn’t want to be a superhero film, it wants to subvert our expectations and draw us into a dark, grounded, and miserable vision of Gotham that I didn’t want to leave.

Matt Reeve’s depiction of Gotham is rather cartoonish. Architecture is fittingly exaggerated, and its inhabitants are underpinned by rampant crime as they hope their political system is somehow able to pull them away from the clutches of inevitable dystopia.

It’s a grim place, one dominated by a seemingly endless cover of darkness and so much rainfall that I now believe that Gotham is located somewhere in Wales. Despite its outlandish qualities, the entire city rocks with a rugged realism. Bruce Wayne exists in a city that is suffering from very real societal issues and a political stigma that is awfully reminiscent of our own landscape. Many have grown tired of the status quo, believing that the establishment will never stand up for their beliefs or enact change that will see the world become a better place. All hope is lost, so the villains have no choice but to take matters into their own hands.

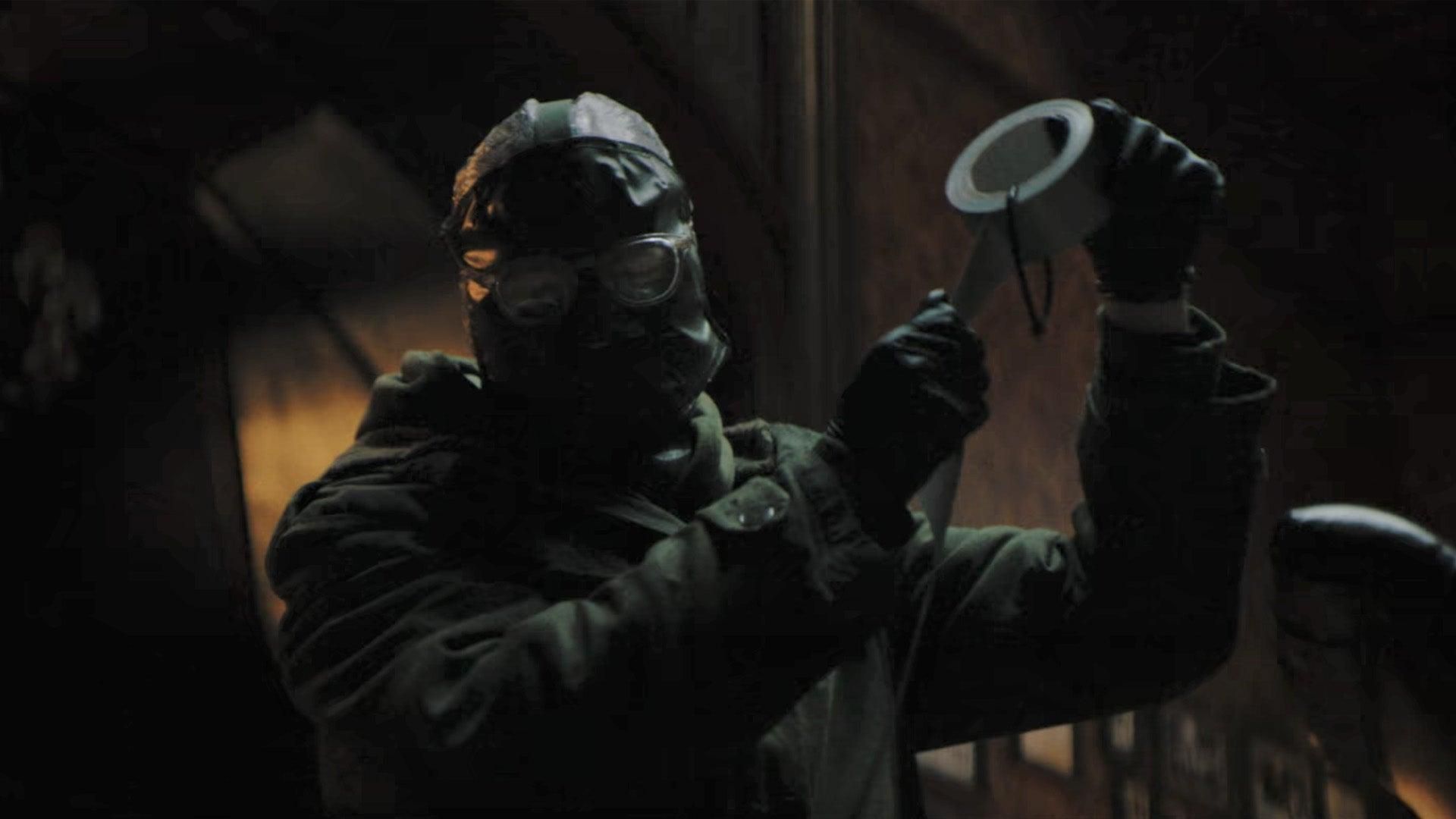

This is where The Riddler comes in. Past iterations of the character have painted him as a neon-green jokester happy to fling around riddles and have a bit of twisted fun. He only ever wishes to outsmart the legendary hero, toying with him at every turn with an attitude that hangs on the knife-edge of nihilism. He’s a devious villain, but one that we’ve rarely taken seriously. Eyes always turn to Bane or The Joker when we want a genuine threat for Batman to tackle, with The Riddler often playing second fiddle to much bigger fish in the pond. This film changes all that, swapping out the playful green for a murderous red that leaves a trail of bloodshed in its wake. The Riddler isn’t afraid to kill, scheme, and unearth the truth because he believes himself to be the hero, one who will be joined by Batman as he unearths a righteous wave to wash away the debris of a city wrought with corrupt pollution. He’s a white man who believes the world is against him, and that’s a big deal.

When the Joker movie was released, there was a fear that embracing the plight of a man who is beaten down by society so much that he turns to violence would be a negative source of inspiration for incels holding similar grudges. Yet the film itself is a damning criticism of precisely that, pointing out how a series of silly decisions see Arthur Fleck accept an ultimatum that he could have walked away from. But he enjoys the chaos, he revels in the possibility of his life becoming a comedy after years of it being defined by tragedy. He’s a despicable figure that only the most warped minds would view as a hero once the credits roll.

The revolution he incites is made possible by a similar group of people who also believe they’ve been wronged, that the government owes them something and the only way to enact change is to take up arms and make higher powers answer for their crimes. The thing is – they’re right. Disclaimer: I am not an incel. Nolan, Phillips, and now Reeves understand the storytelling potential behind Gotham’s saturation of crime combined with a corrupt political system. It’s a cyclical cycle of bloodshed and lies, so ingrained in the city’s foundation that the only way to address its presence is to uproot it all and start again.

The Dark Knight Rises, Joker, and The Batman play on these insecurities, asking a mixture of criminals and the common people to join together for a cause that will make the world a better place. It’s a bitter victory, one that results in further crime and the death of innocents caught up in the ideological crossfire. This thematic exploration has always been relevant, but in the wake of Donald Trump’s presidency and the emergence of 21st century fascism, it takes on a new identity that this latest film is more than happy to lean into.

Revolution is now viewed as an eventuality by a collection of far-right internet dwellers who believe the world is leaving them behind. Games are becoming more diverse, women have no interest in them, and woke politics are infiltrating every piece of media imaginable because the world is changing for the better. For them, it’s a sign of being ignored. They feel as if they’ve been labelled villains purely because they were born as white men, unable to separate criticisms of patriarchy and institutionalized racism from criticism of them, personally.

The Riddler has legitimate grievances with the Wayne Family after being raised in an orphanage that was left behind to rot in the face of empty promises and failed donations, but the expression of his character occupies a place that is pulled straight from reality. Paul Dano’s performance is unsettlingly reminiscent of young white men we’ve seen on the news in the wake of tragic mass shootings, depicted by the media as someone with mental health issues (terrorists of other skin colours rarely have news outlets make excuses for them). It’s a warped perspective we’ve seen time and time again, and the vitriol The Riddler spews out comes from a similar place. Misplaced grievances and internalised resentment that paint all those who differ from you as the enemy, and the only way to cement progress is to wipe them from the face of the Earth entirely.

Before the film’s final act we see him take to his dark web message board, posting a video to fellow incels as he plans his final assault. In the comments we see people talk about piecing together masks, firearms, and ammunition – prepared to kill as the revolution they’ve waited so long for is finally upon them. This excitement is short-lived as they are brought to justice by the very spectre of vengeance they sought to imitate. A lingering symbol of fear who once lurked into the shadows is now a public figure who hopes to make Gotham a better place, accepting that bloodshed isn’t the answer and that he now has a public responsibility to fight back against those who take his ideology and hope to express it in a way that is fundamentally misunderstood. The light that splinters the night sky was meant to be an insignia of fear, but for The Riddler and so many others like him, it became one of inspiration. It is easy to see where this leap in logic was made, and how The Riddler saw Batman as one of his own, someone who hoped to bring Gotham to its knees in order to rebuild it. It’s a fascinating dynamic we’ve never seen the genre tackle before, and it feels all too real.

The Batman isn’t going to inspire incels to rise up and take a stand. If anything, it feels like a profound warning about our current political landscape and the grievances fostered amongst the far-right in the last decade or so. The Riddler will be relatable to certain groups of people in a way that unsettles me, because they will see themselves in a villain who by the end of the film is labelled a pathetic example of revolution who, despite all his obvious flaws and egotistical intelligence, does manage to uproot society in a way his moral opposites never thought possible. When left alone long enough, people like this can translate their beliefs into action. It’s such circumstances that we need to be aware of, lest they result in unfathomable and deeply irreversible consequences.

Source: Read Full Article