It’s fascinating how we gravitate towards games about work. I’m not talking about simulators that recreate real-world professions, but vibrant and experimental efforts where the act of toiling away in exchange for results is built into their very design.

Animal Crossing: New Horizons is all about creating our perfect island paradise, ensuring we check in every day to gather resources and play the economy while also saying hello to residents who rely on our presence to keep on trucking. Stardew Valley focuses entirely on making a living and establishing relationships, which arguably means more than getting away from the hustle and bustle of city life that acts as the game’s conceit. I want to raid dungeons in search of loot and grow the largest pumpkin in existence that I can sell for oodles of previous gold. I wanna be rich, a fantasy that real life is yet to let me experience.

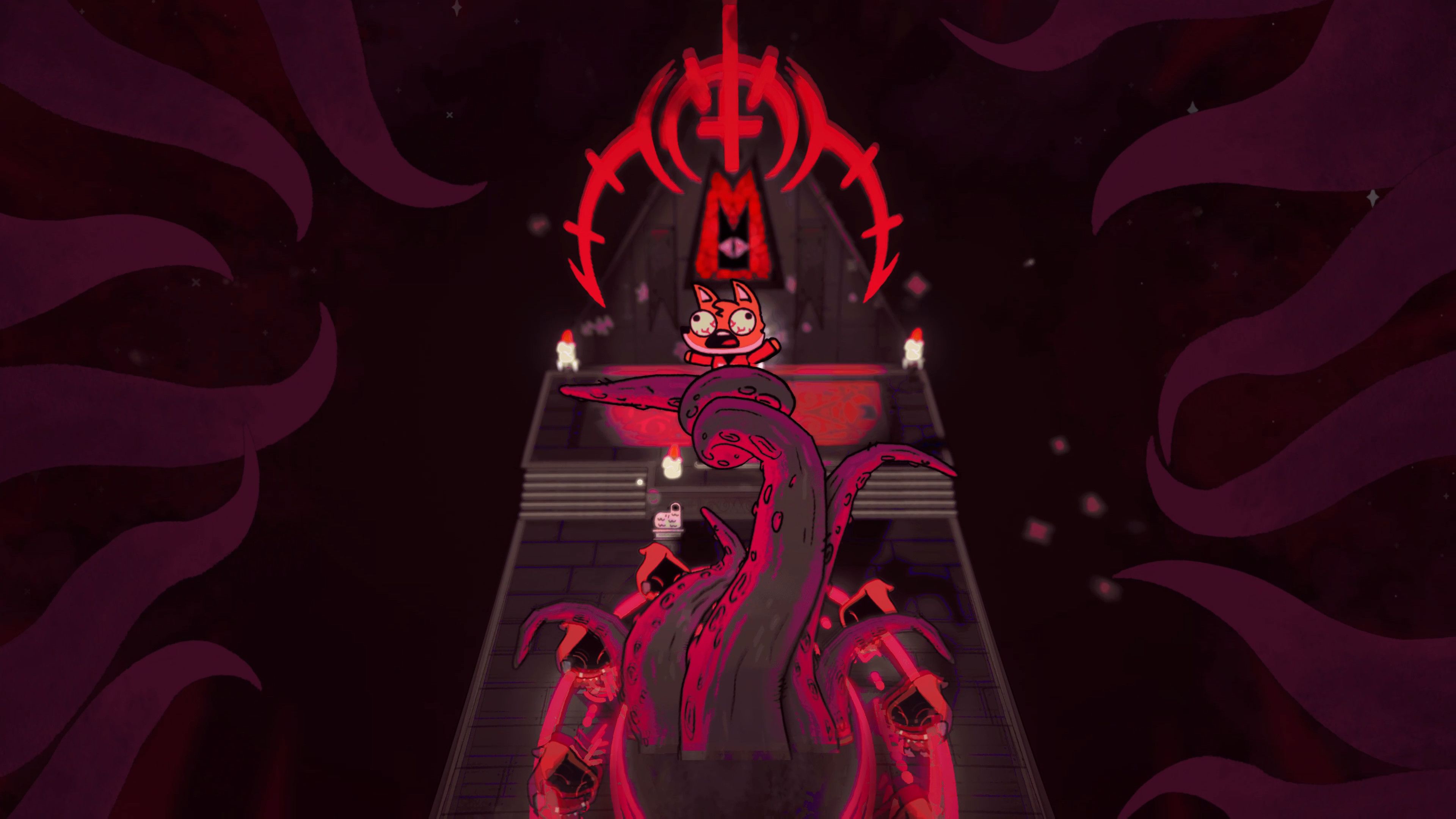

Even Cult of the Lamb, an indie hit that is still capturing the imagination of millions, is centred around a gameplay loop of performing the same tasks over and over to build your reputation and become a stronger and more prosperous deity. We are in it for the grind, but the fact that labour is gamified in such an engaging way means the core idea of tackling it outside our usual work lives is no big deal at all. If anything, we actively embrace and want to see more of it in the games we play.

We’re noticing this trend more and more, and while it’s been the case for decades, Stardew Valley changed everything.

Harvest Moon, Minecraft, and Animal Crossing existed before the arrival of ConcernedApe’s masterpiece, but Stardew Valley would modernise the formula and nail a cadence of countryside living that could pull you in for hundreds of hours. The game’s core focus is labour – becoming a farmhand capable of growing crops, raising animals, and delving into mines in search of myriad secrets. Every action rewarded us with something, and we all know that when it comes to real jobs this isn’t always the case. Video games that focus on labour don’t shine a light on the mundane reality, but instead choose to smother us in euphoria. To show what happens when you work hard amidst an environment that is willing to pay us back for putting in the effort. Stardew Valley absolutely nails that potential appeal.

A daily routine only further cements this depiction of labour, with players coming to establish their own internal behaviours and habits to ensure they are getting the most out of every single day. Watering crops can take up a lot of time and energy, so it’s best to automate the process, while tending to every single animal on the farm is a chore too. Keep the hay stocks filled, and you only need to worry about picking up eggs, milking cows, and shearing sheep.

All things that became second nature as we make regular visits to town in order to flirt with our sweethearts and sell things at the local shop. Stardew Valley is always showering us with small drops of serotonin, keeping us engaged with meaningful steps forward that tempt players to invest just one more day before bringing their session to a close. Unless you are spending your real life dedicated to a job you admire, being able to find satisfaction in a game like this is the next best thing. Audiences weren’t the only ones to realise that potential with Stardew Valley, countless developers also came to take inspiration from its success.

Only now are we beginning to see this evolution come to pass. Games like My Time at Portia, Spiritfarer, Hades, Moonlighter, and I Was A Teenage Exocolonist interpret labour in a similar fashion. Many of these are fantastical experiences, ones that have us chipping away at building a reputation in the underworld, helping adorable animals move onto the afterlife, and being an adorable homosexual on a fledgling colony on the farthest edges of the universe. Labour in these instances is fantastical, but always grounded in expectations we associate with the real world. Things are expected of us, energy is dispersed to earn money or build ourselves up as people, and there is a clear toll to be considered when things go too far. Everything matters in some way, and thus we buy into the fantasy.

I Was A Teenage Exocolonist might be the most poignant example of labour in video games we’ve seen yet. You begin the game as a young child, but are quickly encouraged to start pulling your weight across a colony that needs everyone to pitch in, or it all falls apart. There is time to rest, of course, and the narrative actively encourages time away from hard work in order to avoid burning out or losing your spark, but work sits at the forefront constantly. Thematically it stands up against the pursuit of profit, but recognises the value we come to draw from a successful career and creative passions, with that often put far ahead of material gain. You earn money to spend in this game, but you rarely need to.

Each day you awaken and are asked to dedicate the next month to attending a series of classes, helping deliver supplies, or perhaps even venturing out into the wilderness to hunt animals and procure resources. You earn currency and experience in exchange for your work, while also building relationships with those labouring alongside you. It all leads to something, but the consequences of being a part of this archaic system is explored in the narrative, and even contradicted as the capitalist systems that brought Earth to its knees threaten to resurface in this new attempt at building a home for the human race.

It’s fantastic, and I often had to have a serious think about where my time was going and if I was building to a worthwhile destination. You need to have studied for years to pursue a career in Engineering or Life Sciences, while the local garrison won’t dare have you tag along for patrols without the appropriate training and experience. It takes the role of labour in the game’s design one step further, making it a cumulative aspect of your character with narrative and mechanical significance, instead of a linear indicator of progress that spits out rewards.

Chasing a certain career might make you lose friends or grow distant from family, while there might come a time when your expertise will save lives and change this colony for the better. We buy into virtual work, and the game is so much stronger for recognising that investment and actively hoping to critique the role in which we play regardless of the path we choose to take. Even in our pastimes, we are shackled to familiar vices.

I Was A Teenage Exocolonist knowingly takes inspiration from Stardew Valley, although it doesn’t just incorporate those systems into its identity, it also questions whether a passion for labour, even in a fictional sense, stands a chance at lessening our value as human beings. It’s the next logical step in how this medium tackles things, and to see it approached with such emotional nuance proves that Stardew Valley got the ball rolling on something quite remarkable.

The world isn’t getting any better, and neither is working to keep ourselves alive, and to see video games address how we seek to lose ourselves to imaginative equivalents of real world routines and habits is morbidly fascinating and is poised to teach us so much.

Source: Read Full Article