Behind the intricate graphics and grandiose narratives, many games are inherently about numbers. There’s a figure that you’ll need to reach to complete your mission, with the strategising behind the flurry of in-game activities chiefly being about ways to optimise your runs. It’s something I’ve often thought about when playing the demo for Nobody – the Turnaround, a self-proclaimed “realistic survival simulator”, as a man who had to raise $10,000 within a month—or see his debt continuously snowballing till it becomes impossible to meet.

The stakes in Nobody are as plentiful as they are precipitous; the game revolves around making ends meet amidst extraordinarily difficult circumstances. Players can choose from several scenarios, each with its own set of stories and challenges, but there’s only one to choose from in the demo for now: a man paying back his debts to a loan shark incurred by his own father. Doing so means taking on several odd jobs to pay the fee. While you’re never short of jobs, they generally don’t pay well, and better paying jobs typically require more advanced skills you need to nurture over time.

On top of your monetary concerns, however, you also have to keep your mood, hunger, health, stamina, and a litany of other considerations in mind. As much as you’re tempted to, you can’t just work yourself to the bone, for if these dip below acceptable levels, they can prevent you from making a living. Become too hungry and you can starve to death. Get injured from work, and finding jobs will become exponentially harder. And if your savings dwindle too quickly, you can easily spiral into depression, which may even see you resort to drastic, even illegal measures that can get you arrested. Nobody is built upon making often difficult but practical choices, with basic amenities such as clean beds and a good shower occasionally proving to be an unattainable, even if simple, luxury.

It’s a ruthless experience, but Nobody does paint a realistic portrait of the plight of the working class in China, with its scenarios inspired by actual stories and anecdotes. Loan sharks are endemic in the country, where the developer of Nobody is based, with these illegal money lenders typically targeting low income families who cannot afford to take bank loans. In Lanzhou, one multi-billion dollar criminal lending scheme has seen 89 people losing their lives as they find themselves ensnared in vicious predatory lending cycles. One man, for example, had borrowed 2,000 yuan (US$305), only to see that amount rising to 700,000 yuan (US$107,000) when he could not make the payment in time. This is far from an isolated incident, especially in several parts of Asia where borrowing from loan sharks is still a common practice. Nobody’s scenario is merely a grim slice of this reality. Managing your resources and mood carefully thus becomes a series of calculated life-saving choices, rife with heavy consequences.

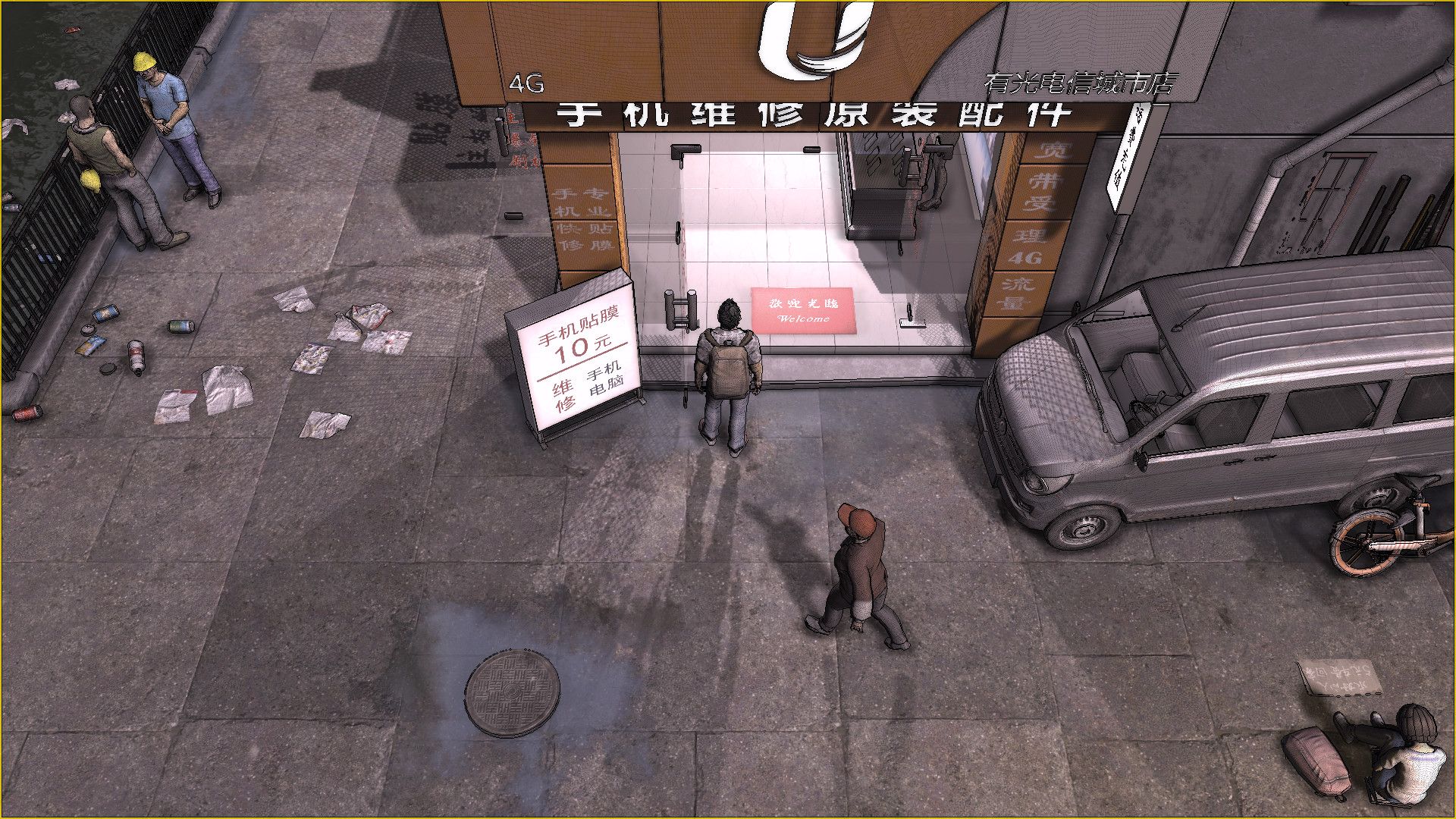

In many ways, Nobody is reminiscent of war survival game This War of Mine, but it also somehow feels more familiar, even intimate, as it takes place in the back alleys and recognisable streets, rather than the war-torn homes of a far-flung city. The main difference is in the way Nobody presents its challenges, which still carries a more hopeful and aspirational tone than This War of Mine; you can, with some hard work, pull yourself out of this rut to become a somebody, perhaps even patch together a semblance of a life with a loved one.

But the problem with survival and life simulators like this is that they’re still based on the myth of pulling yourself up from the bootstraps, as if hard work is mostly what you need to wrestle yourself away from the clutches of poverty and truly awful circumstances beyond your control. This is a feature that feels baked into the very structure of the game, but I would still love to see this subverted, in some way, with its full release later this year. Regardless, this doesn’t take away the deep empathy that Nobody conveys. Many games are power fantasies, but very few games have, like Nobody, encouraged players to better comprehend the day-to-day affairs of those who have been living below the poverty line.

Source: Read Full Article