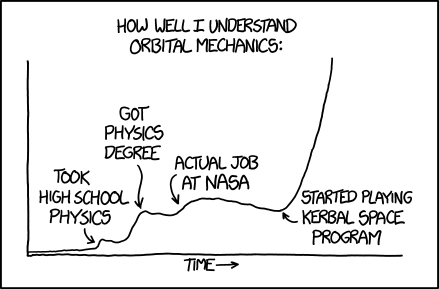

Orbital mechanics is, according to internet wisdom, the (deep breath) “application of ballistics and celestial mechanics to the practical problems concerning the motion of rockets and other spacecraft”. It’s clearly a concept loaded with complex principles and formulas no amount of words can fully encapsulate. Even XKCD cartoonist, Randall Munroe, could not fully grasp it in his years of study in school and university, or as a contract programmer and roboticist at NASA. But the one thing that upended his understanding of this theory and the basics of space flight? Kerbal Space Program.

First launched in 2011, Kerbal Space Program has become one of the most critically acclaimed space flight simulators. Like others of this genre, there is no grand narrative to follow, just a central quest: send the alien race, the Kerbals, to glorious space by building a functioning spacecraft. Eventually, the game was so popularly received, as well as lauded for its realistic physics simulation, that it was given the stamp of approval by the astrophysicists, engineers, and astronauts from NASA—with the developers soon collaborating with the space agency to produce updates based on real-life NASA initiatives.

For all its authenticity, however, hurling a massive, metallic object towards the vast expanse of space still remains challenging—a testament to the difficulty of catapulting a spacecraft into orbit in real life. Having played Kerbal Space Program for a couple of hours myself, my rockets were quickly decimated by the dozens, mowed down by their sheer ineptitude to soar towards the sky. But it’s such realistic elements that also saw simulation games being utilised for training across various industries, including analysis and predictions for medical and aviation professionals.

“Simulators are a special kind of genre. While most games are about creating a particular type of experience, the simulation genre isn’t actually about creating anything at all,” suggests our own Justin Reeve, a self-professed fan of flight simulators and a pilot in real life. “Simulators are about recreating something. This of course creates all sorts of problems […] like whether a given aspect of the flight model is accurate, but it represents, in any case, a completely different approach when it comes to game design. You’re trying to make something as close to reality as possible.”

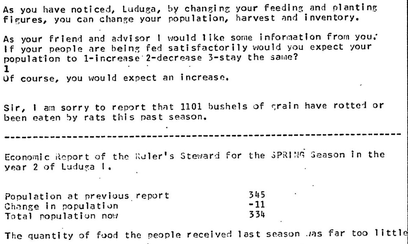

One thing to note is that simulation games had a long and thorough history that preceded even the advent of video games. Take for instance the earliest simulator that was cobbled together in 1910: the ‘Antoinette Barrel’, the first ever flight simulator put together by French aviation manufacturer Antionette, which is literally a half-barrel mounted on a structure that could be manoeuvred by pilots, and help familiarise them with plane controls. Medical simulations, too, had been used to minimise accidents in the 1930s, but it was only in the 1960s where simulations were considered for education as well. This resulted in a text-based economic simulation game called The Sumerian Game (1964), developed by a fourth-grade teacher named Mabel Addis.

That said, The Sumerian Game wasn’t a hit back then, since personal computers weren’t prevalent yet. Instead, it had to be played on a litany of hardware including tape decks, slide projectors and extravagant mainframe computers, which were used chiefly at academies and businesses to crunch through large-scale transaction processing. Scenarios and prompts were printed on pieces of paper, with players keying in their responses into a computer terminal.

Fast forward to a few years later, and Sega released an electro-mechanical arcade flight simulator known as Jet Rocket (1970). The game was notable for being the first flight simulator game created for commercial use, after decades of professional flight simulators used to train pilots, even during World War 2. Jet Rocket also featured cockpit controls, while also being the first open-world title that lets players snipe at various landmarks. Japanese developer Taito also followed suit, releasing a combat flight simulator called Interceptor (1975), which allows players to shoot down enemy aircrafts with a joystick.

But it was in the 1980s that simulation games would reach their apex, their popularity surging with the prevalence of hydraulic motion simulator arcade cabinets, spurred by Sega’s series of ‘taikan’ games such as Space Harrier (1985), After Burner (1987), and the R360 series (1990). Flight and combat simulators, as well as rail shooters, were all the rage then, with Taito launching more arcade flight simulators that adopted 3D polygonal graphics: Midnight Landing (1987), Top Landing (1988), and Air Inferno (1990). Flight simulators then made their way towards personal computers around the same period, from SubLOGIC’s FS1 Flight Simulator (1979), which later became Microsoft Flight Simulator, to MicroProse’s F-19 Stealth Fighter (1988), with increasingly realistic armaments and aircraft features being included. While striving for accuracy, such games have simplified several aspects of piloting to keep them accessible to a larger gaming audience—a philosophy that still persists in many modern simulation games.

Alongside the rise of flight and combat simulators were medical simulation games such as Life and Death (1988), which parallels real-life medical operations with startling accuracy. Central to these games is the need to actually study how to carry out these operations; in a review for Advanced Computer Entertainment, Rik Haynes wrote that for Life and Death 2: The Brain (1990), they had “spent more time back in the classroom than I did curing patients”. Here was also when several other notable simulation games were created around the same time: Utopia (1982), largely regarded as among the first city building and real-time strategy game; Submarine Commander (1982), the first submarine simulator; Fortune Builder (1984), one of the first business simulation games; and of course SimCity (1989), the seminal city-building game that spun off several sequels and series. Even the first parody simulator game surfaced at that time with Advanced Lawnmower Simulator (1988), in which players can mow several lawns, depicted simply by several shapes that look like it’s hastily put together by an aspiring artist on Microsoft Paint. There’s also only one input: the M button. After mowing a few lawns, the mower explodes and the player just dies.

Despite the genre’s eventful history and recent popularity, simulation games never really existed within the purview that more mainstream, triple-A games have occupied. Instead, its influence is much more niche, thriving among enthusiast groups such as trainspotters or aviation specialists, with these games designed to replicate their counterparts in the real world as closely as possible. Rather than the fantastical world building or immersive narrative of most video games, simulation games thrive on authenticity and rigour instead, with many titles typically requiring its players to study and conduct ample research first before diving into the thick of it—much like the aforementioned Life and Death. For Reeve, his interest in simulation games stems from his love for studying the thick tombs of manuals and documentation before stepping into a virtual cockpit. “I could tell you all of the normal and emergency procedures for any of the aeroplanes. I could also quote you the system descriptions and performance figures from memory. While most players would find this incredibly tedious, it actually enhances my enjoyment of these games,” he says. “This kind of approach also broadens my perspective as a pilot in so far as I wouldn’t otherwise have access to any of these aeroplanes […] you aren’t likely to ever fly one of these outside of a game like Digital Combat Simulator.”

But flight simulators aren’t the only sort of simulator games that require their players to rifle through pages of instruction manuals. One of the more well-known simulation games, the Farming Simulator series, even has its own academy program to help ease newcomers into the unexpectedly comprehensive world of farming—complete with operating heavy machineries, harvesting crops and understanding seasonal cycles. The need to read up intensively before playing the game, however, hadn’t deterred a good number of would-be players. Giant Software, the developers behind Farming Simulator, revealed that their player base is made up of both professional farmers—who ordinarily don’t consider themselves as gamers—as well as players who fit the typical gamer profile: those who enjoy playing mainstream, non-niche games. The result is a rapidly growing community around the game; Farming Simulator 22, according to Steam charts, has seen an average of 19,024 players in February this year—a figure that’s comparable to the number of players in Skyrim in recent months.

“[We] have a lot of players that actually [have some] interest in farming, and now they have a game that is about farming,” explains Martin Rabl, head of marketing and public relations at Giants Software. “So that's when they started playing video games, and they wouldn’t have considered themselves gamers before. And I think that helped in growing that niche more, because we introduced more people to gaming. And when that niche grew, other gamers also became aware of it, and saw that this is not just some gag or something or a joke, it's games that people like.”

One of the unique challenges of developing a simulation game as realistic as Farming Simulator is that using agricultural machinery, such as tractors and irrigation systems, as well as becoming familiar with all the other nitty-gritty of farming isn’t just entertainment; it’s also a real-life job, with many elements that probably aren’t that fun. Rabl admitted that while authenticity is always going to be at the core of Farming Simulator, striking the crucial balance between busywork and entertainment isn’t always easy, especially since there’s a significant group of players who want the entire experience to be highly accurate to real life farming.

“Especially when it comes down to the machines, we try to recreate them as detailed as possible. Like every nut and bolt and every movable part should be as realistic as possible, because that's also really important for our players, […] many of them know these machines very well, and they want to see them as detailed as possible,” adds Rabl. These are the players who revel in the often repetitive process of farming: those who wish to fertilise the field three times, plough the field thoroughly, and even want their crops to rot, if not harvested at the right time. “But some others, they want to tone it down, and they just want to play the game.”

Wolfgang Ebert, the public relations and marketing manager of Giants Software, highlighted the way simulation games often let you choose what to explore, in contrast to real life tasks, which are full of necessary busywork you may not want to be caught up in. “I think one point to add here on that matter is that we also have really many optional things. So there are really tons of options for the game to adjust. So for example, just taking weeds, if you don't like it, just turn the option off. Or if you don't like seasonal cycles—because for seasonal cycles, you have to plant and harvest at specific times—you would simply turn it off. Those are optional things for the players to adjust… to tweak the game to their personal playing style.”

One experience that’s not included in Farming Simulator are the random, unforeseen circumstances that plague the job, such as the breaking down of your tractor, or the snapping of the axle during unexpected moments, do technically happen in real life, since they tend to happen outside the players’ control. “At the moment we don't have that [even though] that would be something that can happen in real life. But on the other hand, [it’s also] something that could just spoil your experience by playing the game because it […] just happens, you know? And it's annoying in real life, and it would also be annoying in the game,” Rabl explains.

Giant Software’s dedication to realism in Farming Simulator had led the developer to work with AGCO, a manufacturer in agricultural machinery, which has allowed them to include the company’s new combine harvester within the game. “When they introduced the new combine harvester—the Ideal—they worked with us so that we [could] modify the game even more. We brought the Ideal to the game, but we also made another simulator based on [that, which] went into more detail,” Rabl says. The real-life machine would have apparently cost around “half a million” dollars, but the simulation they made based on the Ideal allows real-life farmers to try out the combine harvester before making that hefty investment.

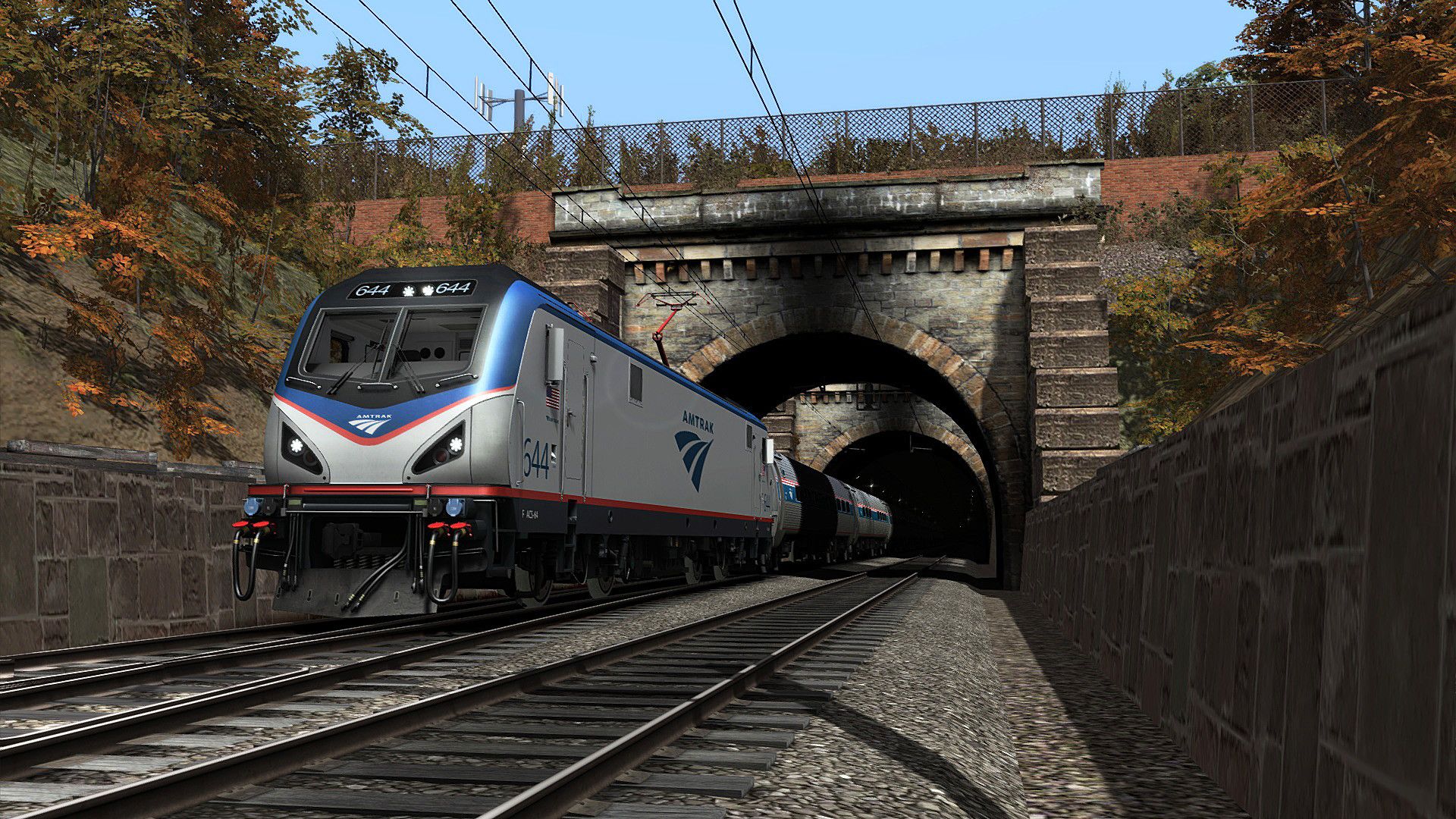

In contrast to more traditional fare like Farming Simulators are a type of simulation games that are less research-intensive but have seeped into mainstream gaming circles, such as PowerWash Simulator, Euro Truck Simulator, Gas Station Simulator, and Train Life: A Railway Simulator. Most of these require players to follow a simple tutorial, and then move towards whatever responsibilities they wish to fulfil. In particular, Train Life was developed with more casual audiences in mind, but also with enough details to keep train enthusiasts engaged. “Train Life is meant to cater to a casual and midcore market, with deliberate decisions made to ignore some of the complexities and conveniences in pursuit of gameplay that we felt was more engaging,” says Joey Bougneit, the lead game designer in Simteract. “We wanted to avoid the complexities of other games on the market, which were hurdles that we felt gatekept some communities from engaging with those titles. This certainly doesn’t mean that those titles are in any way bad, but we had a different market and goal in mind.”

It’s this mix of realism, but without the intimidating barriers to entry, that may introduce more players to the genre. Dean Cooper was first hooked onto simulation games through the indie game Jalopy, which is about crossing Eastern Europe in an old, beat-up car. “It involves replacing the car battery, the tires, the gas, accounting for where to hide smuggled goods,” says Cooper. “The focus of it is trying to make do the best you can with what you have, and what you have isn’t much… aside from each other.” To him, as well as several fans of simulation games who I’ve spoken to, what’s most appealing about the genre is its relaxing, meditative and even therapeutic experience.

“Where Farming Simulator games are about working as a team and acting almost as a group therapy session, Gran Turismo is about the singular focus of the zen in minutiae. By that I mean that every part of the car, from the carburetor to the tire pressure, the tire type, the wheel balance… every bit of the car needs to be focused on and honed in for the specific track that I’m about to race,” Cooper tells me. “That hyperfocus into every detail allows me to mentally compartmentalise all of my problems, my anxieties, my fears and depression, and just stow it all away for another time while in that moment I am working to perfect my car and my driving line.”

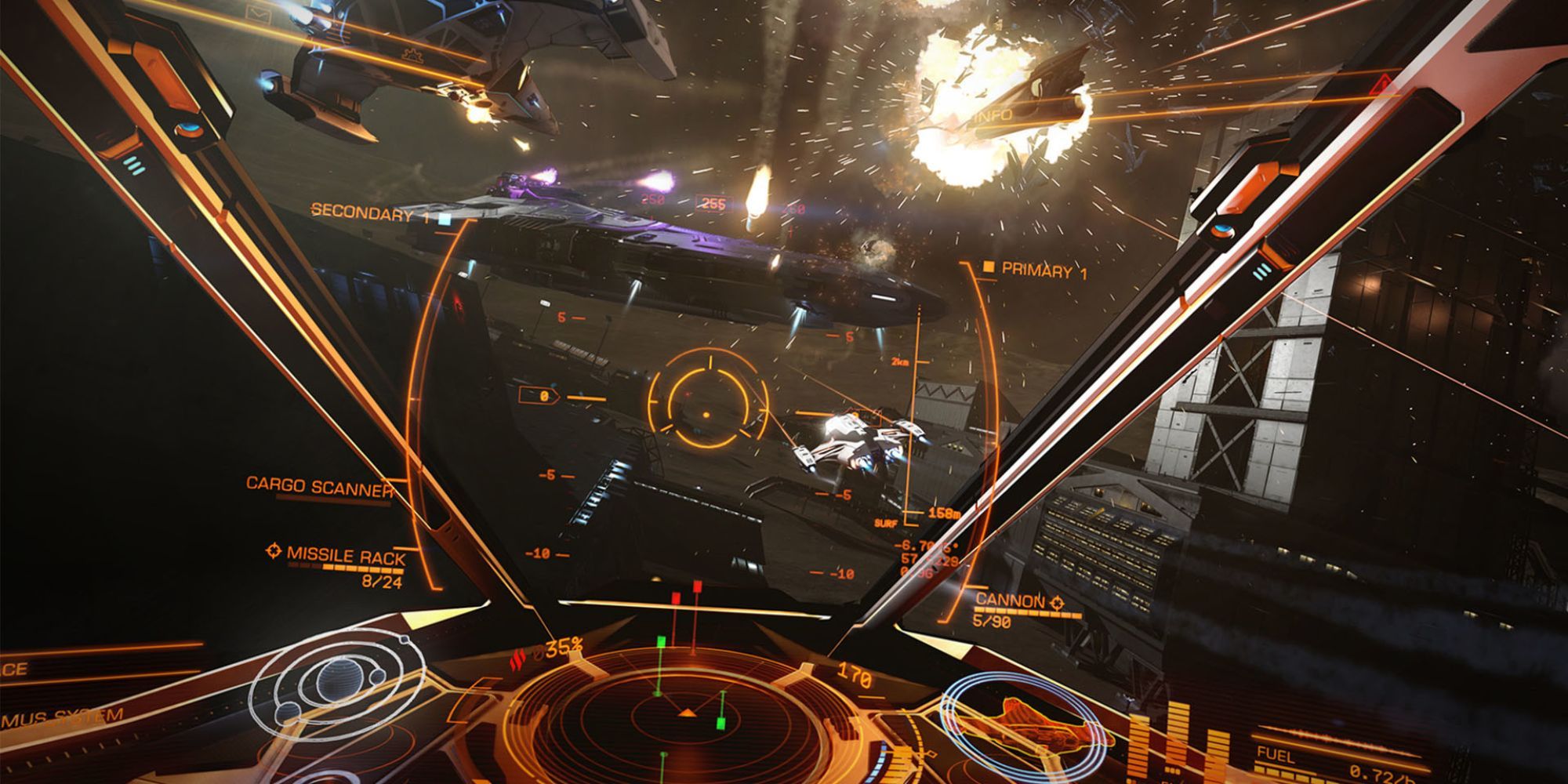

Likewise, simulation game enthusiast Rob Rich enjoys the mundanity of carrying out various tasks in these games, such as Elite Dangerous and Duskers. “There’s something about performing virtual approximations of mundane tasks—especially when they’re futuristic mundane tasks—that I find irresistible. It’s fascinating and entertaining, but I also take a lot of comfort in the ritual. It’s very relaxing for me, and the more nuanced and fiddly, particularly with sci-fi stuff, the better!”

For developers like Simteract, these finicky requirements by dedicated simulator fans probably won’t be a difficult bar to reach. The team behind Train Life is already made up of people who have previously worked on professional train simulators—those that were used to train real-life locomotive drivers. And with Train Life putting you at the head of a railway company, there are plenty of controls to fiddle with, such as making sure that rails are switched correctly, the train is going at the right speed, and activating the emergency brakes when necessary. “We have [the] experience of creating professional train simulation system, so it was easier to jump on projects like Train Life,” says Bougneit. “When we decided to focus on the gaming industry the genre decision was fairly simple. The gaming simulators market is booming and we follow what’s in our DNA—we want to be a key part of the genre’s expansion.”

Rabl is aware that people who play Farming Simulator tend to lean towards it because they aren’t as stressful and hectic as other genres, but he still relishes the game’s capacity to educate more people on the intricacies of farming, as well as answering basic questions about where our food comes from. He shares his astonishment over the idea that one of his friends, a steak-loving Argentinian, has never seen an actual cow before—to which I inform him, in a somewhat abashed tone, that I didn’t actually get to see one myself until I was late into my adulthood, too. He laughs.

“That's when I also realised, like, I grew up in a village, so I know a little bit about farming, but when you grow up [in other places], you just eat food from the supermarket or in a steak restaurant, but you don't know where these things come from.“

And in a cyclical twist, the burgeoning trend of parody simulation games like Goat Simulator and Rock Simulator is making a comeback, much to the displeasure of simulation game fans. On a Reddit thread titled ‘Is there a way to separate joke "simulators" from the simulation category?’, players can be seen commiserating over the growing difficulty of filtering out these parodies from “actual” simulation titles. “Apparently I filtered out Game Dev Tycoon, an amazing game just because I didn't want to see certain garbage,” wrote one user. Such games aren’t the first of its kind—if you recall, Advanced Lawnmower Simulator was one such title back in 1988—but to many fans, they also feel like a mockery of the genre.

Our own Joe Parlock, a fan whose favourite simulation game is Farming Simulator, pointed out that many simulation games were often the butt of the joke for many gamers. This is particularly so with Train Simulator and its huge number of DLCs—which now amounts to 747—and which is said to be the most expensive game on Steam, if you were to buy all of them, since doing so will set you back at least by a few thousand dollars. “The response to this is a great way to tell the difference between a sim player and someone who stumbled across it on Steam,” says Parlock. “You’re not meant to buy every bit of DLC for a sim game. They’re not treated as games in the same way Destiny or Genshin Impact are, they’re platforms for an only casually related hobby. People who don’t play any other games will play a sim as their primary hobby, and pick up the expansions and DLC that they’re interested in.

“It’s always been a pet peeve of mine when people point and laugh at sim games for their DLC, and it shows an ignorance towards a genre that is quietly chugging along and not hurting anybody else. They’re small bastions away from the usual dramas and nonsense of wider gaming, and I hope they stay like that.”

Just like the increasing popularity of simulation games in the 1980s, the recent boom in the genre has also seen more players introduced to these games, with more developers getting into the fray and producing niche titles, such as Cities: Skylines, House Flipper and Bus Simulator. After all, I’m one such player myself; I wouldn’t consider myself a fan of simulation games yet, but even I could appreciate the relaxing mundaneness driving my truck in American Truck Simulator through long stretches of asphalt, more keen to see the banal sights of clouds and mountains outside the window as a driver, rather than oversee a massive delivery and trucking empire.

“Simulators, and any relevant subgenres, are definitely gaining in popularity, but the market is still finding its place I feel,” says Bougneit. “With all of the new technology emerging, this decade is going to be exciting for games with simulation elements.”

Source: Read Full Article