At the beginning of Mass Effect 2, the Normandy – your spacefaring base of operations for the entire first game – is destroyed. Protagonist Commander Shepard stays back to make sure her crew escapes with their lives. Shepard isn’t so lucky. She’s still inside when the Normandy cracks open, sucking her out into the cold vacuum of space along with computer terminals, electronic parts, and shattered sections of the ship’s hull. It’s as if someone presses the mute button on a TV remote, the void swallowing sound itself along with the debris, leaving Shepard floating there in complete silence, waiting for death.

In the sci-fi thriller game Deliver Us The Moon, there’s a similar sequence where there’s a breach and you’re thrown out of an orbital station like a hooked fish being pulled from its natural habitat. One minute you’re safe, surrounded by the beeping of computers, and the next you’re sucked into the silent unknown among dangerous space rubble, oxygen supplies dwindling.

“The contrast of silence and what is happening is amazing, seeing the planet in the distance with space rubble, fantastic,” Deliver Us The Moon game director Koen Deetman tells me, referencing the scene that inspired him most in Mass Effect 2.

Dora Klindžić, a writer and scientist from Croatia, was also inspired by Mass Effect. Like many, she was introduced to the games during her high school years. She grew up with them, and they taught her to write stories that grow with the reader. “The fact that the games let me choose what’s important for me felt like I was learning about who I am as I was growing up,” Klindžić explains. “This drew me into writing interactive fiction, where a commonly uttered credo is that a good interactive fiction game feels like a psychological test. I continue to write stories with a goal to reflect the player back [at] themselves, teach them new perspectives and help them grow (up).”

Klindžić points to the Geth loyalty missions with Legion, a party member who’s from a network of hive mind robots that have carved out their own civilisation among the stars. “[This was] my first encounter with themes of AI consciousness and free will. Particularly the iconic line: ‘Does this unit have a soul?’ captivated me so hard that I continued to write about robots for years, and my first published works which launched my career were the fruits of this inspiration,” Klindžić says.

This spark of imagination goes far beyond fiction writing, however. Another thing that stood out to Klindžić was how Mass Effect makes a distinction between “dextro-amino” and “levo-amino” alien species. Turians and Quarians evolved from amino-acids with a right-hand spiral, in comparison to humans with a left-hand spiral. This snippet of Mass Effect lore ultimately led to Klindžić helping to create a real-life planet scanning gun that can search for extraterrestrial lifeforms.

“This introduced me to the concept of chemical chirality as a signature of life in the universe, and a decade later this fascination would lead me to join a project group designing a detector which could one day look at distant planets and tell us whether a homochiral presence on that planet exists,” Klindžić explains. “In other words, scan a planet from lightyears away and see whether there is life on it, and whether this life is levo-amino or dextro-amino.”

Another person who Mass Effect was formative for is Ivona Denovic, a concept artist who also played the series during her college years. Denovic was studying art seriously and the scope of the work done in Mass Effect captured her imagination. “Everything stunned me [about] how well it was put together – the visual language, the score, the mission design,” Denovic tells me. “I’m replaying it now and it’s all coming back to me – [it] feels like coming home.”

Denovic studied the Mass Effect 3 artbook religiously in those early years, poring over the artwork, astounded at the level of detail on display in each scene. “I was just blown away by how much thought went into every character, every environment, even seemingly random props,” she says. “I learned a lot of my trade and what kind of artist I want to be because of this game.”

What’s interesting speaking to people whose work has been influenced by Mass Effect is how varied they are, each of them picking up on a different part of the game, whether it be art, a specific set-piece, or the lore. But among all the answers I received, the most common thing to crop up was the characters.

“By the time the last one came out I had started Vlambeer, was halfway through Ridiculous Fishing, and was traveling the world,” game developer Rami Ismail says. “But it was the same Shep throughout, right? My Shepard. It was nice to be able to hop back to a character that was me through half a decade of osmosis and deal with galactic security issues instead of sending a fax.”

Jonathan Burroughs, director and co-founder of Variable State, thinks this persistency is what makes the original Mass Effect trilogy so powerful. Before the Marvel Cinematic Universe and Star Wars became the behemoths they are, he first saw the technique used in movies like Before Sunset and Before Sunrise, as well as In the Mood for Love and 2046.

“In the original instalments of those films, I’d become attached to characters at a particular moment in their lives, ending the films with an idea about how events would unfold after the credits rolled,” Burroughs says. “And then in the sequels, often set years later, I returned to those characters to find whilst off-screen, they had grown and changed and ended up somewhere totally unexpected. There’s this wonderful bittersweet feeling to reconnecting with characters I had loved; joy at being in their company again, but also poignancy at seeing how their paths had diverged from the ones I’d imagined for them. So the idea of embracing discontinuity, of putting in gaps spanning years, and showing the outcome of off-screen events, was bold and exciting to me. And produced emotions and an experience that was meaningfully distinct to stories with direct continuity.”

In Mass Effect, this off-screen character growth even extended to random NPCs, allowing you to pick up threads and unfurl the lives of a virtual galaxy with each new game. While the locations and characters were changed, playing the sequels for the first time felt like returning home to visit relatives you haven’t seen for a while. “Exploring the consequences of the passage of time, allowing for off-screen character development, withholding information from the audience and allowing them to fill in the storytelling themselves are all things which have stuck with me – which feel like they hold a special power – and which I try to find ways to include in the stories I’m involved with wherever I can,” Burroughs says.

That gap is powerful because of your absence. We spend all three games as Commander Shepard, making her decisions and deciding who she is, right from the character creation screen – deciding if she even is, in fact, a she – on through to every conversation. In allowing us to make that character’s decisions across three games, our choices echoing throughout them all, Mass Effect created an unbreakable link between us and our on-screen avatar.

“I think it meaningfully integrated player choice throughout the series,” actor Ashly Burch tells me. “I know there are mixed feelings about the ending amongst some fans, but I was always amazed and inspired by the butterfly effect of my actions through all three games. Choices in the first game that seemed small or isolated had extremely significant consequences in the third game. There are whole swaths of people that didn’t experience certain content based on who survived what encounters. I remember when Mordin died in the third game I was devastated, but I didn’t realise there was a scenario in which you might shoot him in the back. And then yet another scenario where you could kill Wrex in cold blood!

“The Shepard some people chose to play would be unrecognisable to my goody two-shoes Commander. I know that lots of games give opportunities for divergent play styles, but I’d never played a game that honored those play styles so much and really shifted the narrative depending on player choice.”

Jennifer Hale’s performance as the female Commander Shepard is Burch’s favourite in any video game, and much of that is down to this variety – the range needed to make a character feel consistent across all those branches. “If you’re given a script in which a character is a ruthless murderer, but you know that they justify their actions because of a specific trauma they endured when they were a child, you can always ground yourself in that context,” Burch explains. “For Shepard, the player not only gets to choose how the Commander behaves throughout the game, they even get to choose her backstory. So Jennifer – I imagine – had to find what few consistent tentpoles there were – she’s a soldier, she wants to stop the Reapers, etc – and build a person that would make sense no matter how the player chose to move through the narrative. She managed to ground every choice the player could make in a character that felt consistent and true. You could be a complete murderous, violent monster or a sacrificial, empathetic leader and she made those choices – and every shade in between – make sense. She felt like a real character, a real person. That is so hard to do when the player has that much control over the story.”

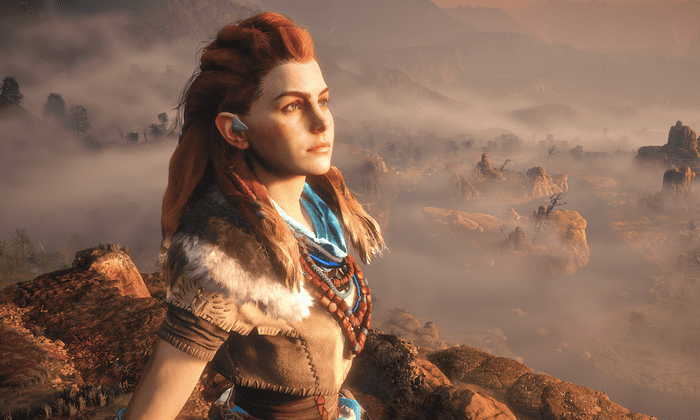

Experiencing this through Commander Shepard, Burch would later apply the lessons she learned in her role as Aloy in Horizon Zero Dawn, another game where the player can shape the lead character – albeit to a lesser extent. “Being familiar with Jennifer’s performance really helped me as we discovered Aloy through the recording process for Horizon,” Burch says. “Finding that balance between honoring context and making her feel grounded no matter what the player chooses is such an interesting needle to thread. And Jen is an absolute pro. I thought about her performance frequently. It’s absolutely masterful. I learned a lot from it.”

Much like Burch’s anecdote about Mordin’s death coming as a shock during her first playthrough, everyone has a moment that sticks with them, and it’s rare you speak to two people who will give you the same answer when asking for highlights. But one thing does crop up more than most: the suicide mission at the end of Mass Effect 2. I think that’s down to permanence. Not many games are brave enough to let you experience loss, but the Mass Effect series had an entire game dedicated to bonding with people who you can ultimately lose if you make a couple of wrong decisions. That fear of losing them made party members feel more precious, somehow.

“While it hasn’t necessarily been an immediate influence on my type of design philosophies, it’s a game I still think a lot about in terms of structure,” game designer Liam Edwards says. “The ability to weave a personal narrative based on decisions you make was not something I’d experienced before playing Mass Effect 2. The idea that each crew member was a truly living character with origins, morals, likes and dislikes, and their own thoughts was incredibly eye-opening. The fact that you weren’t necessarily choosing a crew based on their stats and ability to help you in a fight, but instead how much you as the player had bonded with them. You were essentially choosing which friends you wanted to take on challenges with.”

Party composition goes out of the window when you create an RPG with such an eclectic, brilliant mix of varied characters. Look out across the fandom and there are Jack jobbers, Garrus groupies, and Liara loyals. There are even people who like space racist Ashley Williams, for some reason. Mass Effect is a masterclass in making you care about characters over the long term, taking them with you – not because of their guns, but because of their one-liners.

“My most enduring memory is the moment before the suicide mission in Mass Effect 2,” Rich D May, a lead programmer at Rebellion, remembers. “As with most BioWare games, I’d managed to fail spectacularly at all of the relationships – art imitating life! – and my ‘reward’ was a scene of my Shepard wandering morosely around her quarters, staring into space as she contemplated what was to come. That sense of her being alone – the isolation of command if you will – was more powerful than any love scene.”

While Mass Effect 2 undoubtedly gets most of the love, none of that would have been possible without the first game which, while mechanically inelegant, laid the groundwork for an entire galaxy of adventures. Its influence can be felt across the entire games industry in the work of artists, actors, writers, game directors, developers, and you can even see it in the games themselves.

“In many ways, Mass Effect created the template for the modern triple-A title,” May says. “The sequel tightened everything up, of course, but the original is the genesis of the mixed action RPG genre that we see so much these days – tight, real-time combat, relatively simple upgrade trees, fully-voiced and animated conversations. You can see that these days in every Assassin’s Creed or Spider-Man that comes along. It set the benchmark that all ‘big’ games have to follow. I can’t talk much about my work at the moment but suffice to say it’s always there as a touchstone in the back of my mind – ‘what did Mass Effect do?’ If we can get even near that, we’ll have done alright.”

Like the Normandy sailing through the stars, extending humanity beyond the confines of our home planet, Mass Effect’s influence is further reaching than just video games as well, inspiring not just game developers, but people who will one day become our own astronauts, scientists, and engineers.

“Completing the series made me realise I want to pursue a career in space exploration, and I was quite surprised to hear several other people repeat the same sentiment in my freshman class of Physics in 2013,” Dora Klindžić explains. “I believe the impact of Mass Effect is much broader than people realise, and its writers did an incredibly good job in instilling this romantic view of science and exploration in an entire generation of players.

“Since the series ended, I’ve had to chase those same thrills by working on deep-space tracking of Martian orbiters, designing tools for the search for extraterrestrial intelligence, and developing an instrument to be sent to the Moon. And of course, to keep writing science fiction, to pay it forward to the next generations of budding scientists.”

Next: Remembering The Rebel Inside – An Interview With Courtenay Taylor, The Actor Behind Mass Effect 2’s Jack

- TheGamer Originals

- Mass Effect

- PC

- Xbox One

- ps4

Kirk is the Editor-in-Chief at The Gamer. He likes Arkane games a little too much.

Source: Read Full Article