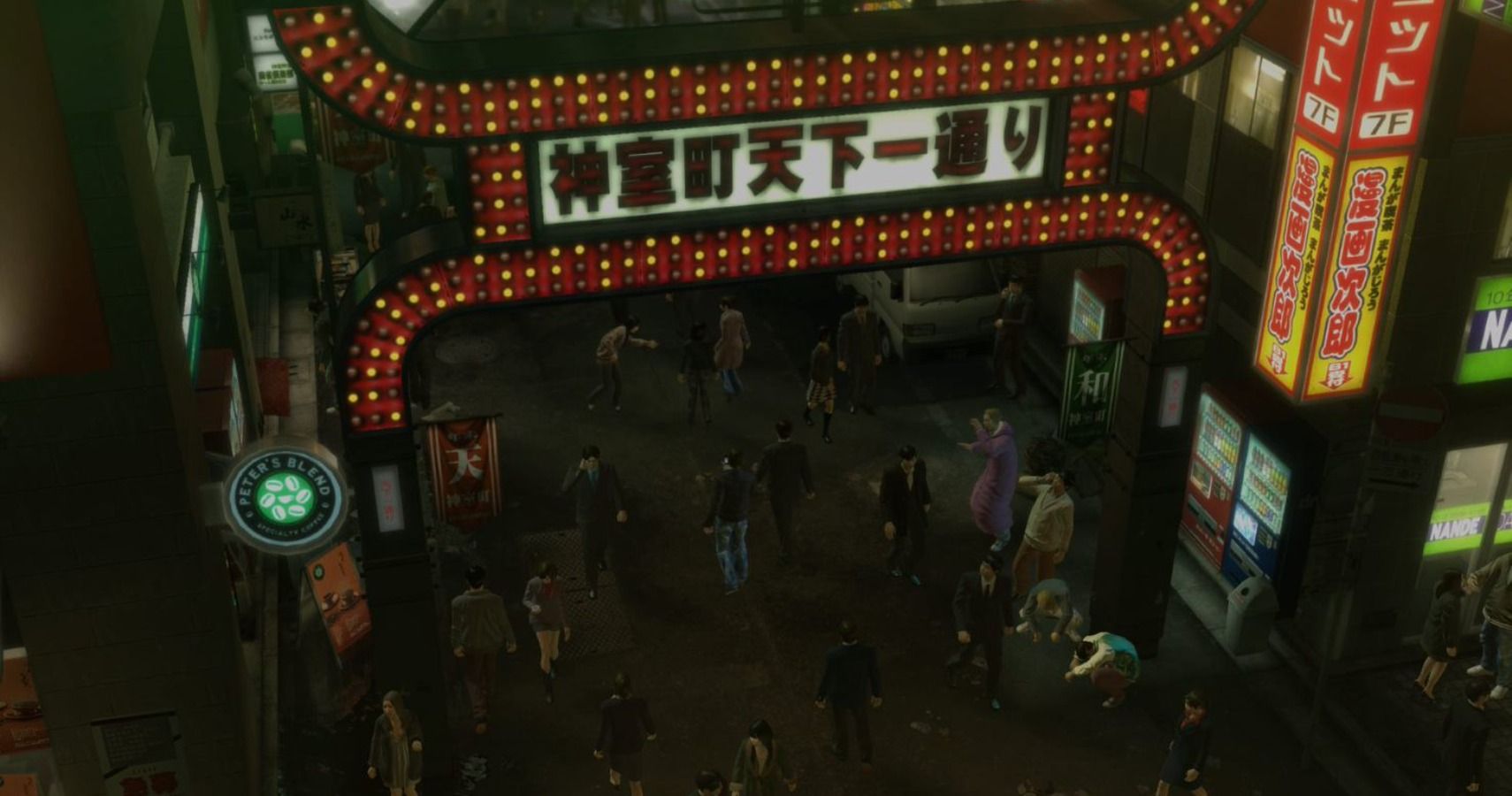

Yakuza is one of those series I came inexplicably late to. Despite knowing for years that it would be up my street, I didn’t download my first Yakuza game until November 2020, at which point I decided to finally prowl the streets of Kamurocho as Kazuma Kiryu in Yakuza 0. Since then, I’ve slowly but surely been making my way through each game – I’m on Kiwami 2 at the moment – and despite the fact I reckon the combat is rubbish, Yakuza has quickly become one of my favourite series.

There are plenty of other films, games, TV shows, and books set in Tokyo, although I’ve always been most fascinated by Haruki Murakami’s accounts of the city. I’ve actually got a well tattooed on the outside of my right forearm, which is a reference to both Norwegian Wood and The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle. Over the last few years, though, I think I’ve started to develop Desmond-from-Lost syndrome. Just like how he holds off on reading Our Mutual Friend, his last Dickens novel – and a top three Dickens novel at that – I’ve slowly realized that Murakami’s oeuvre is finite, and if I just tear through it all in one go there’ll be no stories left at the end. I’ve got a thicc copy of 1Q84 sitting on my bookshelf that I want to read every day, but probably won’t have the conviction to even start until I’m 50. I’m 25, so that’s double my current age – brutal.

As a means of remedying this, I’ve started consciously looking for similar stories. Despite the fact that I’m about to discuss Yakuza, this hasn’t usually entailed me wanting to specifically visit a fictional Tokyo so much as it’s influenced me to look for stories about magic in the modern mundane. Weirdly enough, Persona 5 is another game that managed to capture this for me. Obviously that’s set in Tokyo too, but it’s coincidental – I’m talking more about atmosphere than any strict geographical boundaries. Studying in the school library and punching politicians who have turned into Dragon Ball Z characters two hours afterwards – that’s the kind of thing I’m on about here, although Murakami and Yakuza are a bit more subtle than shooting Old Testament God in the face with a bullet made of the Seven Deadly Sins. Not that that’s not cool, by the way – it’s just not what I’m on about here.

It’s easy to see Yakuza as some sort of bruisin’ cruisin’ beat-’em-up where Kazuma Kiryu talks business with his fists, although I think it’s much more complex than that. I’m thinking of Tachibana’s weird powers in Yakuza 0, most of which are never truly explained. At one point he just waves his hand and all of the lights in Kamurocho go out, and then he has a fall because he’s spent all of his energy. My question is: what energy? How have you done this, Tachibana? Do all real-estate agents have the ability to control the light fittings in houses they’ve sold?

This is something I’ve grown to love in Murakami – Toru Okada will talk about ironing shirts for ten pages, then we’ll get a line of magical realism where he falls through a wall or something, and then he’ll have a quick beer before proceeding to look for a cat named after his brother-in-law for a chapter or two. The magical realism is simultaneously the standout moment from this sequence and the part we skim over almost involuntarily. We’re invited into mundanity to lower our guard, so that even when something truly extraordinary happens, it’s yet another facet of the mundanity on either side of it, because the mundane is magic, too. This is something that Yakuza excels at – from the fact we can increase our combat capabilities by talking to a guy in clown makeup, to the fact that Heat actions revolve around an aura that reminds me of Hunter x Hunter’s Nen, even the most minor stylistic choices are enchanted with weirdness.

I mentioned my well tattoo earlier, so it’s probably worth delving into that in more detail. In Norwegian Wood, Toru Watanabe and Naoko are in some kind of field at the beginning of the novel. Naoko decides to bring up the apocryphal existence of a magical well that nobody is able to see. The well as an object is largely unimportant here – what matters is its context to the conversation. Conversely, in The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle, Toru Okada descends into the pitch blackness of a deep well – this one is fully visible, mind – in a local garden in order to think in darkness and in silence. In both cases, we’re talking about ordinary, everyday structures – but in both cases, these inanimate objects are imbued with a sense of ethereal magic because of the way they are considered.

We can apply this same thought process to lots of different areas in Yakuza. From West Park to Serena, there’s something about each and every ostensibly ordinary place here that makes it feel as if there’s a whole quiet and unseen world bubbling beneath it. I reckon Tojo Clan HQ is a great example of this, too, although the absolute best area to consider with this in mind is Yakuza 0’s Empty Lot.

While it has immense monetary value, there’s also something mystical about the Empty Lot. The game begins there before you even know about how significant it is, but the sheer grit of it all demands your attention. And yet it’s not just gritty – the confined space, brightly lit by unseen light sources, viewed via obscene camera angles that don’t appear elsewhere in the game’s direction… it’s designed to be disarming, which is why it’s so weirdly enchanting. The second you leave the Empty Lot, you know it’s not just some arbitrary place that the game started out in – but you also recognize that in some ways it must be arbitrary because of how visibly ordinary it is. As you play through the game you’ll begin to recognize that these aren’t mutually exclusive conditions, which is in and of itself a case of genuinely excellent writing.

This is why moment-to-moment play in Yakuza feels so natural, but all of the narrative peaks and valleys spike sufficiently hard to break past the graph’s boundaries. It’s very blunt in its delivery of information, but the story is shrouded in an invisible sense of mystery that goes far beyond the current question at all times. This mystery doesn’t assert its presence, which is where the magic comes from. It’s the exact same as in Murakami, where even the most brazen examples of magical realism feel intentionally anti-climactic in order to elevate all of the otherwise mundane scenes into something much more pronounced. Basically, by making magic seem ordinary and refusing to explain it, even the most normal things in a game become inherently mysterious due to the simple fact that they could potentially conceal yet another mystery. It’s a structure that very few texts execute well, but one which both Murakami’s best works and the Yakuza series – at least the early games – are evidently founded upon.

There are parts of Yakuza that seem too absurd to be real – why do Billiken and The Florist have magical elevators that lead to some underground universe nobody knows about? But they’re no less absurd than anything in Murakami, where there are not only secret underground structures, but a gargantuan worm with a vendetta against the Tokyo Security Trust Bank – the only way to stop it is to team up with a superhero frog. The same short story collection includes a story about sipping whiskey by a bonfire and pondering the meaning of life, which ends with the protagonist anticlimactically drifting off to sleep. It’s the juxtaposition of things so normal that they should be boring and things so ridiculous that they should seem stupid that creates a world that feels believably magical, and I think that’s something that Yakuza manages to capture just as well as Murakami’s most revered works.

Next: Horizon Forbidden West’s Underwater Levels Are Probably Going To Be Brilliant

- TheGamer Originals

- PC

- SEGA

- Yakuza

- Xbox One

- Ps5

- ps4

- Xbox Series X

Cian Maher is the Lead Features Editor at TheGamer. He’s also had work published in The Guardian, The Washington Post, The Verge, Vice, Wired, and more. You can find him on Twitter @cianmaher0.

Source: Read Full Article