In 490 BC, a messenger named Pheidippides ran from Marathon to Athens to report Greece’s victory over the invading armies of Persia, and was immortalized when a race of approximately the same distance was named in honor of his achievement. But this is not the most taxing or egregious physical exercise to have originated in Greece — that accolade goes to Hades’ central premise of having Zagreus belligerently battle his way through the unforgiving realms of the Underworld, where death is not the end of life, but rather a sure route back to a cruel, painful, and grueling new beginning.

Hades is marathonic in more ways than one. Originally launching in December 2018, it has been in Early Access for the guts of two years. In that time the game has seen a range of iterations and evolutions, and has gradually grown into something far more sophisticated than its earliest form. If the original release of Hades was as primordial as the Chthonic Gods who inhabited it, the latest and most complete version of Supergiant’s complex dungeon-crawler is its long-coveted peak.

This lengthy, laborious development is mirrored in the core premise of Hades. Hades is long, arduous, and unrelenting. It often requires a herculean effort just to make it to the fiery fields of Asphodel, less than halfway through your odyssey through the Underworld’s most ruthless locales. And yet Hades remains unendingly rewarding, at all times giving you reasons both to live and to die. Whether you win, lose, or finally realize that the two end states are not necessarily mutually exclusive, Hades teaches you to both appreciate and vilify effort, and that meaning is often found through success and failure in equal measure.

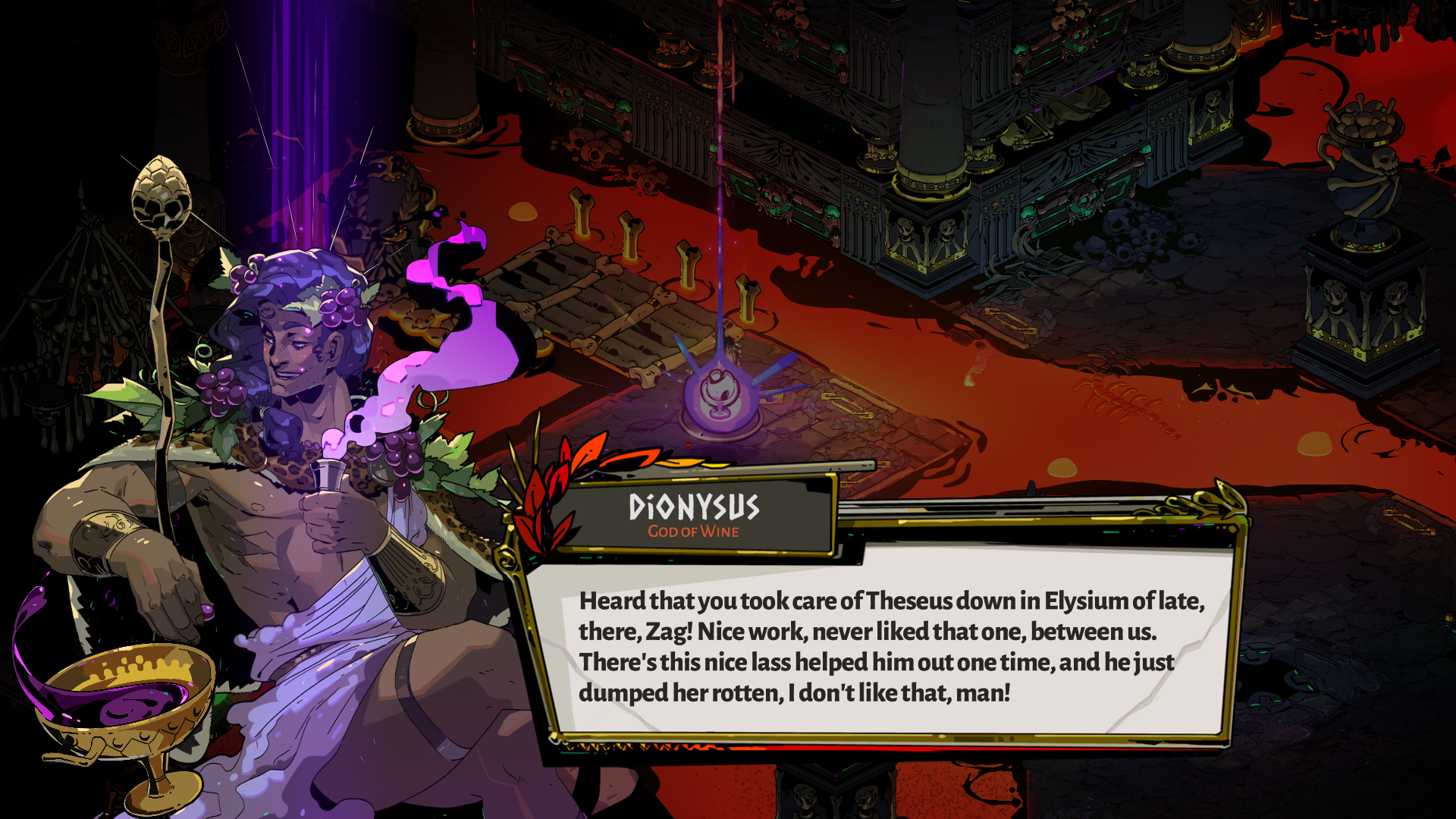

Hades, like the rest of Supergiant Games’ work, is meticulously and carefully crafted into a game that combines fluid, versatile combat with a riveting and refreshingly inventive story. It takes illustrious figures from the Olympian pantheon and juxtaposes them with their Chthonic counterparts, but does so in such a way that its Gods are more like Love Island contestants than the overtly serious representations of them we see in most media depictions. Dionysus is a purple-haired, toga-wearing beefcake who sips on wine and speaks in tones that scream Gnarly Waves, while Aphrodite’s electric wit is immobilizing, brilliantly capturing what Plath called the serpent in the swan.

The story itself is an innovative one — as well as reintroducing these long-established characters in an entirely new way, it’s told from an approach I’ve never truly seen before. This is accentuated by its aforementioned marathonic development process — you see, with Hades, you fight through the Underworld, and whether you live or die… well, you’ve got to fight through it all over again. And again. And again.

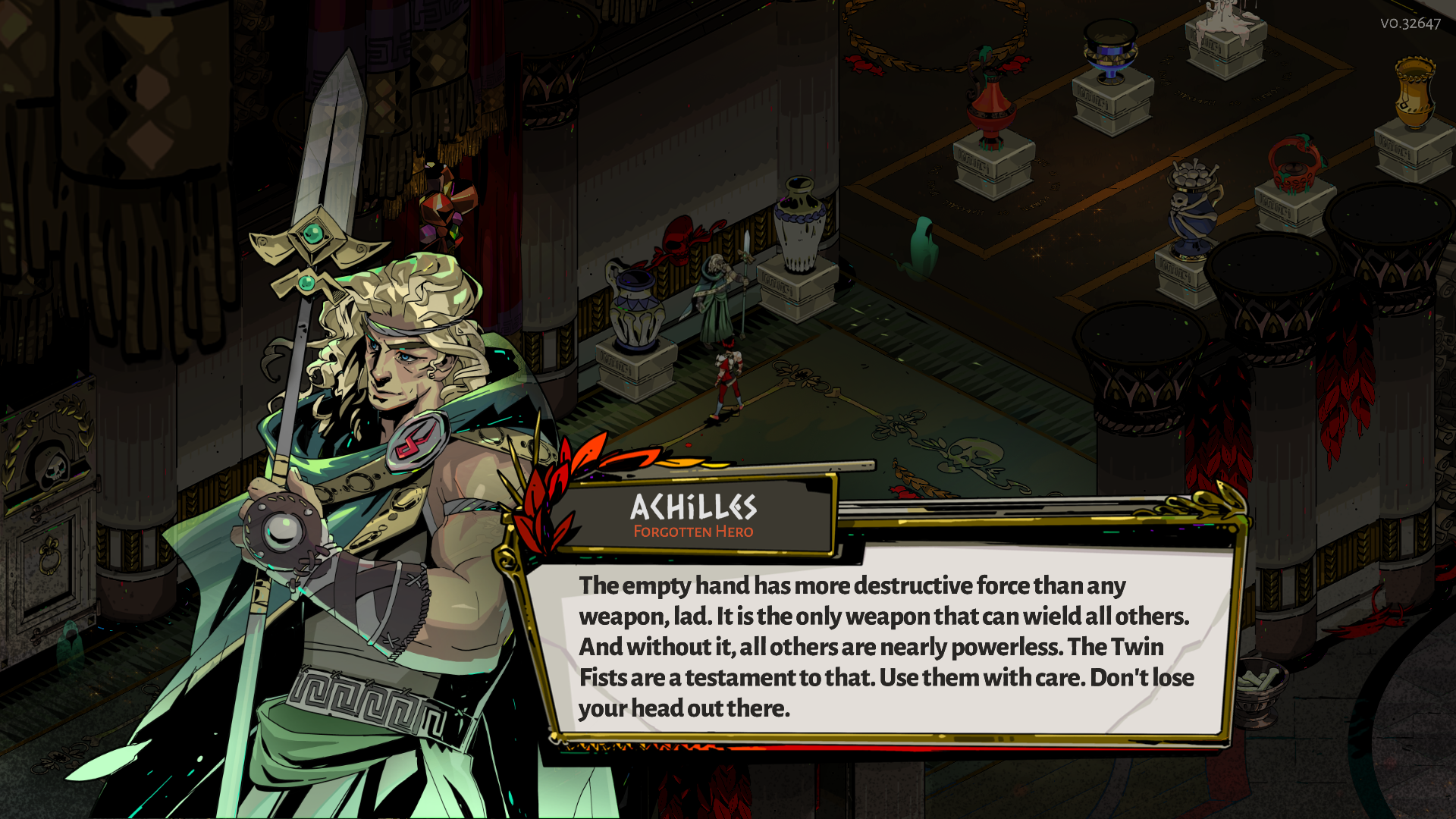

Every time you end up back in the House of Hades, you can speak to each of its inhabitants: Orpheus, the singer cursed with being eternally separated from his muse; Achilles, the legendary Greek hero who teaches you how to fight; and Hades himself, the Titan-slaying God of the Dead who also happens to be your dad. Your relationships with these characters primarily develop outside of the game’s main structure — after being killed and returning to the House of Hades, you will be able to go through a section of dialogue with everyone present. Usually you will only be able to speak to each person once, but if you gift someone a bottle of Nectar or Ambrosia, you’ll get an extra prompt and strengthen your relationship with them.

The design of this is remarkable. Talking to these people is what ultimately progresses the story, but you can only talk to them once per visit. So after you’ve exhausted everybody’s dialogue, which should only take a couple of minutes, the only thing to do is to head right back into the maelstrom — to try to escape yet again, before inevitably being sent on a one-way-trip back to the House of Hades, where Hypnos will laugh at whatever shade managed to kill you, while Nyx tries to offer you solace in the wake of Hades’ inevitable beration of you.

It’s so simple, and yet it is completely enthralling. Full runs of Hades generally take about 20-30 minutes, meaning that it’s fairly easy to squeeze one in. I regularly talk to Megaera the Fury, before thinking to myself, “One more run won’t hurt.” So I do another run and return to the House of Hades where everyone has one dialogue prompt again, but then Meg says something far more intriguing than before and cuts off right before elaborating on it — the only way to learn more is to do another run, but you don’t mind that because each and every run is distinctly different but consistently excellent.

There are reasons for both of those qualifiers. The runs are different because you can go in with one of six weapons, all of which have four unique forms. There are 69 chambers between you and the exit from the Underworld, but they are procedurally-generated for every single run, meaning that the maps are never the same as before. The enemies, upgrades, rewards, and bosses are all different — and so it doesn’t get boring because there’s nothing to be bored about. It is the single most repetitive game I have ever played, but that repetition is its biggest strength. You get all the benefits of learning how to proceed and understanding the structures and systems at play without having to suffer from the staleness of watching the same scenes over and over again, because the scenes in each run are always different. You might not see Dionysus for six hours, but when he eventually shows up and says something new it feels as if the game progresses by leaps and bounds in a matter of seconds.

What connects these instances to one another — these conversations with your Olympian cousins you are so desperately trying to reach — is fast, ruthless, and skilful combat. You usually only have a light attack, a heavy attack, and a ranged cast, but the rewards for progressing through a chamber are so vast and varied that you can play ten runs in a row without the combat feeling even remotely similar to a previous run. From lightning arrows to frost-inducing spears, to a massive shield that causes enemies to suffer from hangovers if you clock them in the head with it, Hades offers just enough versatility to ensure that every session feels different to the last, while simultaneously being strangely and warmly familiar.

The entire experience — from chats in the House of Hades, to conversations with the Olympians, to brawling with sentient chariots wearing the almighty boxing gloves that took down Hyperion — is further complemented by the game’s distinct art style and spectacular soundtrack. The former is visually arresting in a way that you’ll often stop and stare just to peer off into the distance, the diverse color palettes between each and every realm brilliantly portraying how colossal these extraordinary landscapes are, while the latter is one of the most powerful parts of the entire game. Every track is composed in direct accordance with how each world actually feels, and the music for each boss fight governs pacing with tact. I have beaten bosses in 40 seconds that felt like 40 minutes, because the music is so remarkably good at making everything seem bigger, and more precarious.

Hades is, to put it plainly, a masterpiece. It has a refreshingly unique trajectory, tells a compelling story with an alluring cast, and has such a good handle on moment-to-moment play that it is never anything less than genuinely excellent. It’s a game that grows the more you play it, as opposed to being something that suffers from a slow descent into tedium. And for that reason, it is a genuine forever game.

With Hades 1.0 finally out, Zagreus’ harsh and tiring journey has finally come to its utterly extravagant end. And yet it seems that Hades will never end. It will constantly give us reason for one more run, one last vainglorious attempt at escaping the cruel clutches of the Underworld. Its years in Early Access taught it how to become cyclical, but in such a way that the path changes with every revolution. And now, thanks to its remarkably and genuinely affecting conclusion, every death is just one more reason to try again.

Source: Read Full Article